At the Movies with Andy Warhol

Carlos Valladares tracks the artist’s engagements with Hollywood glamour, thinking through the ways in which the star system and its marketing engine informed his work.

Fall 2025 Issue

Jordan Carter, curator and cohead of the curatorial department at Dia Art Foundation, New York, engages with the new artist’s book Cady Noland: Polaroids 1986–2024.

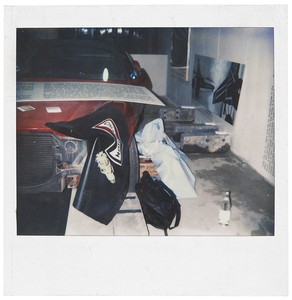

Polaroid taken by Cady Noland, c. 1986–2024

Polaroid taken by Cady Noland, c. 1986–2024

The contemporary cultural meaning of “obscene”—deriving from the Latin “obscenus”—has been said to be obliquely yet fittingly linked to the ancient Greek “ob skene,” literally meaning “off-stage” and referring in Greek theater to events that were deemed too explicit or violent to take place in front of the audience and were conveyed instead by dialogue or other narrative devices. In this vein, Cady Noland assembles sculptural mise-en-scènes that become surrogates or understudies for the obscenities of daily American life and maladaptive media rituals, registering through culturally codified means the violence that goes unseen or that we choose not to see. Cady Noland: Polaroids 1986–2024 makes us voyeurs of the behind-the-scenes social lives of Noland’s object coterie, observing how they behave in their natural environment, outside the neutralizing confines of museums, galleries, or collectors’ homes. While her Polaroids are devoid of people, there is a menacing sense that perhaps someone has just left the room or is about to enter, between the acts. There is no explicit narrative, yet the book’s structured, sequential band of image couplings creates an anxious sense of coincidence and correspondence, reference and relation, as though we’d been clued in to something sinister.

Part manifesto, part compendium, Noland’s critical stagecraft of the page renders a nonlinear, self-styled archive. It can be read within a genealogy of catalogues-as-exhibitions in the tradition of Seth Siegelaub’s similarly spartan Conceptual art publications Xerox Book (1968) and January 5–31, 1969 (1969), or as a perverse take on Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise (1935–66) and its idea of the compressed antiretrospective. Notably, this is not Noland’s first foray into artist’s books that promiscuously slip between document and object, between two-dimensional codex and phenomenological experience. “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil,” Noland’s 1989 treatise on the ludus tactics of psychopathology and the American media-celebrity-industrial complex, was transfigured into her sprawling multimedia installation at documenta 9, Kassel, in 1992, in which the text was screen-printed onto metal sheets leaning against the walls of an underground parking garage outfitted with a red Camaro and a toppled, tortured van. In a hauntingly recursive and metatextual gesture, images from this cacophonous exhibition are interspersed in this new edition: we see different views of a panel of that text strewn atop the sports car. Unbound and metallized, the sequential order of the text became unfixed in the documenta installation and the panels variably lent themselves to combinatory readings, in a manner akin to Joseph Beuys’s Arena—where would I have got if I had been intelligent! (1970–72), a hundred panels carrying hundreds more photographs that document the artist’s career up to 1972. Arena was similarly installed casually, leaning against the walls of the Galleria L’Attico, a former garage in Rome, in 1972 and staged the following year in an underground parking lot beneath Rome’s Villa Borghese for the international exhibition Contemporanea, in both cases presaging the chronologically defiant logic and layout of Noland’s Polaroids, as well as their car park scenographies.

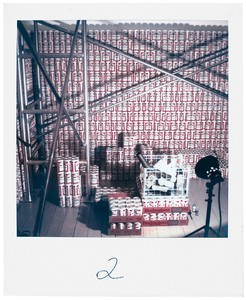

Polaroid taken by Cady Noland, c. 1986–2024

Polaroid taken by Cady Noland, c. 1986–2024

The Polaroids predominantly feature barbarously unceremonious yet palpably staged vignettes in which finished works commingle with what appear to be components or fodder for future works against makeshift industrial backdrops. Objects make repeat appearances throughout the book, and in their recurring roles suggest a theatrical cast of characters in a seedy thriller that unfolds across the otherwise sterile white spreads, with comparable real estate given to both image and margin. Certain pages are left imageless, like blanks for the reader’s projection, becoming a litmus test for our cultural conditioning. Noland’s dyadic compositions play with and deconstruct the architecture of the page; in one instance what appears to be the same metal pipe is cut off at the frame in two opposing Polaroids, bridging the imaginary space of the gutter invisibly.

A material grammar of sinister semiotics develops through juxtaposition, sequencing, and repetition. There is a cadence that picks up and begins to read like visual poetry, filled with metal relays and ricochets. Varying angles and perspectival shifts are a throughline here: not only does Noland’s objectifying viewfinder frame what we can and cannot see but these multiple vantage points suggest the possible presence of more than one set of eyes in an arenalike spectacle. After all, Noland did trade in museum benches for stadium bleachers for her 1996 MATRIX exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. On a handful of Polaroids Noland marks the distances and measurements between works in proportional notation, registering the significance of her staging. In other instances she annotates Polaroids with tagging language, further aligning the book with an evidence repository as we are tasked with deciphering her shorthand and self-invented cataloguing methods.

Polaroid taken by Cady Noland, c. 1986–2024

Throughout, we see Noland’s iconic works and typologies in repose—obscene, offstage—at times on pads, in provisional positions of indecent exposure, like a celebrity unwittingly snapped by paparazzi. The detail shots and close-ups crop and frame in ways that mirror tabloid shots, or perhaps the scrutinizing images of evidentiary photography. This is not unlike the clip-on method, as Noland describes it in “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil,” in which individuals are “reduced” to “photo-objects” by tabloids’ crops and zooms. Reduction is a key formal aspect of Minimalism, a genealogy that Noland radicalized. She manipulates her objects the way tabloids manipulate celebrities, reifying household names into fragmented objects of scrutiny, desire, and violence—tactics-cum-formal-strategies that she describes in detail in “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil.” Indeed, her description of the “game” as a “synthesis of tactics” could also apply to her own material operations as staged and serially documented in her Polaroids. In this way, “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil” functions almost like the discursive counterpart to the visual manifesto that is Polaroids. The latter is the id to the former’s ego, to put it in psychoanalytic terms.

Indeed, Noland treats household objects like the tabloids’ household names, trading in embodied idols for Budweiser beer cans, canes, walkers, and garage trappings. In doing so she not only cultivates a chilling equivalence but also helps us better understand how she sees her work, and how we might begin to see her work with greater acuity. The “game” for Noland, though, is not only a structural and social device but a visual and sculptural methodology. Her Polaroids—works in their own right—fastidiously document fiercely nonchalant material relations. Obsessive iteration of forms, and repetition of their images to ever-more-slightly different positions, reflect to us our own maladaptive compulsions.

The event-based nature of Noland’s work is palpable in these photographs that animate visceral moments with inanimate objects. As the scenes progress, certain Polaroids begin to unfold like shady Eadweard Muybridge sequences. A wheeled cart filled with hubcaps and scrap—a mobile scatter piece—pirouettes in place on one spread, personifying the tension between physical or social mobility and cultural paralysis. These images creep into borderline-pornographic closeups of violently intimate material mashups, as curved metal tops curved metal, and support devices collapse to resemble broken ribs. Noland’s precariously but precisely arranged installations elaborate a tension between control and collapse, perhaps reflecting how, as she writes in “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil,” “The psychopath being the machine that it is, cannot imagine that it will cease to function, but in keeping with its obsession with control, it will short-circuit itself at the last moment if it is unquestionably about to be ‘offed.’”

Polaroid taken by Cady Noland, c. 1986–2024

Polaroid taken by Cady Noland, c. 1986–2024

A plethora of photographs featuring monumental walls or stacks of Budweiser cans—monetarily worthless yet conspicuously consumed and culturally emblematic—demonstrate how, to return to “Towards a Metalanguage of Evil,” “The game depends on investing in things which accrue in value, or in wasting things in an obvious way (but not at your own expense, only to exhibit a genuine surplus).” The beer can is Noland’s pungently ubiquitous variation on the units of Minimalism. Some of her Polaroids emphasize this by picturing works that swap beer cozies for transparent cubes, as cans embalmed in acrylic prompt us to imagine Hans Haacke’s condensation cubes with alcohol sweats.

Noland’s Polaroids are the product of a meticulous process of configuration and reconfiguration in which the slightest tweak has a gestalt impact. This recalls another of her hypothetical psychopathological scenarios:

There are times when X sees that the configuration of elements—be they persons, objects, or events, are in a pattern of environment hostile to the development of his program. X has two choices in this case: he may vacate the situation, or he can wait until [a] shift occurs which makes the environment more adaptable to his plan. A change, however seemingly inconsequential to the outsider, might convince X to move.

Waiting for reconfiguration as a strategy has a relationship to the decision to use shock therapy on a mental patient. Here, through the vehicle of electric shock it is hoped that some reconfiguration in the brain may chance to be therapeutic.

Reconfiguration as a strategy distills Noland’s sculptural and photographic impulse. Her rigorously and unwaveringly specific arrangements bear the promise and threat of reconfiguration.

Noland’s Polaroids exhibit equal parts excess and restraint, maximum violence and minimal means, destruction and distillation, control and collapse, power and precarity. Throughout her photographic dramaturgy, Noland demonstrates her singular ability to be capaciously critical and sinisterly silent—obscene.

Artwork © Cady Noland

Cady Noland, Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York, September 10–October 18, 2025

Cady Noland: Polaroids 1986–2024 (Gagosian/Rizzoli 2025)

Jordan Carter joined Dia Art Foundation, New York, as curator and cohead of the curatorial department in 2021. In 2025, he curated Renée Green: The Equator Has Moved at Dia Beacon and Amy Sillman: Alternate Side (Permutations #1–32) at Dia Bridgehampton. His forthcoming projects include presentations of the work of Agnes Martin and major new commissions by D Harding, Fujiko Nakaya, and Haegue Yang.

Carlos Valladares tracks the artist’s engagements with Hollywood glamour, thinking through the ways in which the star system and its marketing engine informed his work.

Miriam Bale reports from Cannes on the 2025 edition of the international film festival, highlighting three standout films.

Harry Thorne addresses the practical and conceptual links between the visual art of Peter Doig and the work of various musicians on the occasion of Peter Doig: House of Music at Serpentine, London, an exhibition opening on October 10, 2025.

Anna Weyant’s first solo institutional exhibition, at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, was curated by Guillermo Solana in close collaboration with the artist, and places more than twenty paintings by Weyant in dialogue with a selection of works from the museum’s permanent collection. Sydney Stutterheim considers the artist’s contemporary exploration of suspense, identity, concealment, and temporality.

Brian Dillon celebrates the sonic revolutions initiated by Beach Boy Brian Wilson.

Tracking works by Chris Burden, Bruce Nauman, Maria Nordman, and Eric Orr as outliers and outcroppings of the California Light and Space movement, Michael Auping argues that darkness—the absence of light and space—is a key element of the aesthetic.

The jewelry designer Jean Schlumberger permanently changed the face of High Jewelry with his daring approach to materials and techniques. His engagement with flora and fauna from the sea to the sky, and his choice of unparalleled gems, found an eager audience during his lifetime and continues to glamour the eyes and minds of jewelry lovers today. The Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier explores his life, legacy, and the persistence of his studied yet whimsical work.

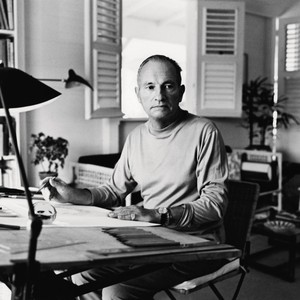

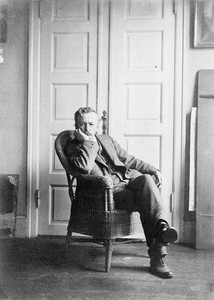

The Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916) has been on Ed Ruscha’s mind as he creates a new body of work for an exhibition at Gagosian, Paris, this October. Christian House visits Copenhagen to consider the quiet and persistent power of Hammershøi’s art.

A major retrospective of the work of the Colombian fiber artist Olga de Amaral has landed in Miami by way of Paris. Presented in collaboration with the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, this career-spanning exhibition will be on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, through the fall of 2025. Here, Ekaterina Juskowski delves into the six decades of Amaral’s life, work, and inspirations.

This fall, Florence will celebrate the work of Fra Angelico with a major retrospective—the city’s first in seventy years—at both the Palazzo Strozzi and the Museo di San Marco, opening on September 26. For the occasion, Ben Street writes about the resonance of Fra Angelico’s work in modern and contemporary art.

On the occasion of two exhibitions—one at Gagosian, London, and the other at Kistefos in Jevnaker, Norway—the Quarterly shares an essay included in the forthcoming book Kathleen Ryan: 2014–24. Here, Harry Thorne writes on Kathleen Ryan’s artistic process, methods of assemblage, and how her studio resembles an excavation site.

Gillian Pistell celebrates the life and work of Kay Bearman, a pivotal force in the cultural life of midcentury New York.