Game Changer

Frank Auerbach

Curator Richard Calvocoressi remembers the extraordinary talent of Frank Auerbach.

Summer 2025 Issue

Gillian Pistell celebrates the life and work of Kay Bearman, a pivotal force in the cultural life of midcentury New York.

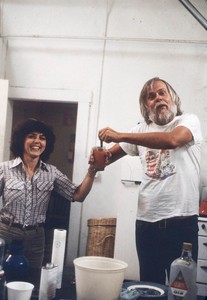

Kay Bearman, Andy Warhol, and Ivan Karp at Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, 1965. Photo: © Bob Adelman

Kay Bearman, Andy Warhol, and Ivan Karp at Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, 1965. Photo: © Bob Adelman

Kay Bearman began working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1960. She had just graduated from Smith College a few months before and decided to move to New York, rather than return home to Memphis, because she was “going out with somebody who was here.”1 The relationship ended soon after but Kay stayed, despite not knowing anyone else in the city. She started to look for a job, mainly sticking to arts organizations to keep some semblance of relation to her degree in art history. She tried the Frick, but didn’t speak German; she tried Artnews, but there were no openings. So she went to the Met, where she was given a job in the museum’s slide library typing up labels.

With a couple of intermissions, Kay worked at the Met for the next sixty years, staying there until 2021—only a global pandemic could keep her from the institution that had become her second home.2 She not only witnessed but also took part in many important moments in contemporary American art. We know the names of the people—men—whom Kay worked with after years of hearing of their often history-changing accomplishments: Leo Castelli, Philippe de Montebello, Henry Geldzahler, and William Lieberman, not to mention artists such as David Hockney, Jasper Johns, and Frank Stella, to name just a few. In many ways Kay made those accomplishments possible; she was the rock that supported them, doing the dirty work and minutiae that made their jobs run smoothly. And it all started from the desk of the slide library.

In 1960, the Met’s slide library was a hub of activity within the museum. Curators from every department would pop in and check out slides for lectures and whatever classes they were teaching. Among those curators was Geldzahler, a favorite of Robert Hale, head of the Department of American Paintings and Sculpture, but seemingly of no one else. Geldzahler was tasked with keeping the Met current on contemporary art. He took a liking to Kay; perhaps she was already displaying her charming, diplomatic but get-the-shit-done attitude. Soon, Kay became what he called “Assistant Henry.”

Geldzahler introduced Kay to his New York art world—which was, in effect, the New York art world. She accompanied him to artists’ studios, parties at artists’ studios, and meetings with collectors. In 1965, however, Castelli’s assistant Nina von Eckardt left her position. Kay later reflected that it was perfect timing; she and Geldzahler had stumbled upon a few “personal conflicts” so she moved to the Leo Castelli Gallery, trading one art world insider for another.3 Kay stayed with Castelli for four years, sharing his desk and her opinions on the art and artists that came through the gallery’s door.

“The ’60s and who Leo was at that time, and who Leo was showing, and what was going on in the art world, at least to me, was the most exciting period of the art world,” Kay reminisced later.4 And it certainly was. She was there for Andy Warhol’s Flowers Paintings and Wallpaper and Clouds exhibitions (1964 and 1966), as well as Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings show (1968), among other history-making presentations. She was at Castelli with Ivan Karp, who would go on to open the acclaimed OK Harris Gallery in SoHo; “the Davids”—White and Whitney—whose respective careers in art curation and criticism skyrocketed in the following decades; and a young Patterson Sims, then still a graduate student, who would likewise enjoy a celebrated curatorial career. Years later, Sims recalled his first encounter with Kay: “I asked a young woman at the desk if I might be directed to Ivan Karp. Kay Bearman . . . laconically pointed at the space’s center room, which I’d always considered off limits. Kay, along with her then Castelli colleagues . . . would all become powerful presences in the contemporary art world.”5

Geldzahler called Kay back to the Met in 1969. Tasked with curating one of the shows honoring the museum’s centennial, he had decided to focus on New York’s contemporary artists, and Kay worked with him to get New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940–1970 hanging on the Met’s walls. “Kay’s sense of organization and her hard work made it possible to do the show on such short notice,” Geldzahler acknowledged soon after the show’s opening.6 Kay’s hard work was noticed elsewhere in the museum and she was moved to the office of de Montebello, who was then the vice director of curatorial and educational affairs. Although she filled that role only briefly, she quickly proved herself invaluable to de Montebello—a relationship that would keep her connected to the Met even after she left with Geldzahler to join the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs.

I quickly realized that she, perhaps more than the art that I was working with, was one of the Met’s greatest treasures. She was a trove of not just institutional but art history, and her stories were legend.

Kay quickly rose through the ranks during her time with the city. First, she oversaw the Institutional Services department, which distributed the city’s funds to its various cultural institutions. By 1982 she had moved to the New York State Council on the Arts, where she was named the deputy director for visual arts. It was in this position that Kay really grew her art-world connections; the job took her all over the state, and everybody had to go through her to get approval for state money.

By 1984, the Met’s newly appointed curator for twentieth-century art, William Lieberman (who had been hired away from the Museum of Modern Art), needed reinforcement as he negotiated the construction of the Lila Acheson Wallace Wing, which was to be dedicated to twentieth-century art and would open in 1987. De Montebello, who was then the museum’s director, reached out to Kay. Her official title was administrator of the department of twentieth-century art, but in reality she was the museum’s lifeline to Lieberman, who was notorious for his eccentricities. Kay did not leave the Met again; in her remaining thirty-seven years there, she stayed with her department as it saw new curators arrive and evolved into the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art. But her presence stretched beyond that department. She was the Met’s first woman courier to oversee art transportation across the Atlantic, and she helped start the museum’s Antonio Ratti Textile Center, which required a digital database that Kay helped extend to the rest of the museum—what would become “The Museum System” (TMS), a collections-management program that is now used by a vast range of art institutions around the world.

I met Kay in 2013, when I joined the Met’s Modern and Contemporary Art department as a research assistant. I quickly realized that she, perhaps more than the art that I was working with, was one of the Met’s greatest treasures. She was a trove of not just institutional but art history, and her stories were legend: chauffeuring Johns’s pet marmoset to South Carolina; calling Mrs. Warhola to reassure her that “Andy’s OK” every day her son was on his first trip to Europe after he was shot; and attending her first Happening, where Lucas Samaras whispered to her, “Tell Henry I’m going to kill him” (Kay thought he was serious and frantically searched for Geldzahler to warn him).

Kay did not think of herself as an integral part of this history; she was never one to seek the spotlight, preferring to pull the strings from behind the scenes. But that does not mean history can overlook her. Kay was there, she did many amazing things, and made even more amazing things happen. She adapted as the times and her role evolved and grew. Sadly, Kay is not alone. There are many people littered throughout art history who remain unacknowledged, and too often they are women.

Kay passed away in 2023. During one of her last days, she looked through old photographs from throughout her life and said, “It’s so nice to have so many memories.”7

1 Kay Bearman, in Sharon Zane, “Metropolitan Museum of Art Oral History Project,” March 12, 1998, Bearman family archives.

2 Bearman retired in 2016 but stayed on as a volunteer for the Modern and Contemporary Art department.

3 Bearman, in Zane, “Metropolitan Museum of Art Oral History Project,” March 26, 1998.

4 Ibid.

5 Patterson Sims, “Appreciation: Ivan Karp (1926–2012),” American Art Journal 27, no. 1 (Spring 2013): p. 104.

6 Henry Geldzahler, letter to Mrs. Leo Bearman, November 12, 1969, New York Painting and Sculpture files, Correspondence: Positive, Metropolitan Museum of Art Modern and Contemporary Archives.

7 Bearman, quoted in “Kay Bearman Obituary,” The Daily Memphian, October 4, 2023. Available online at www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/dailymemphian/name/kay-bearman-obituary?id=53260210 (accessed February 22, 2025).

Gillian Pistell joined Gagosian in May 2017 as a researcher and writer. She received her doctorate in art history from the Graduate Center, CUNY, in February 2019. Prior to Gagosian, she worked as a research assistant in the Modern and Contemporary Art Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and has contributed to several scholarly publications, including Pen to Paper: Artists’ Handwritten Letters from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

Curator Richard Calvocoressi remembers the extraordinary talent of Frank Auerbach.

Scott Rothkopf, Alice Pratt Brown Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, remembers his friend, Dorothy Lichtenstein.

Mark Francis remembers his late friend, the indefatigable and radical curator Kasper König.

Curator and author Peter Galassi, coeditor of the recent collection Ulf Linde: Essays from a Lifetime in the Arts (König, 2023), reflects on the life and work of the Swedish art critic and museum director.

William Breeze pays homage to his friend the filmmaker and author Kenneth Anger, reflecting on his revolutionary work in color, Magick, and spirituality.

Scholar Wendy Jeffers is working on a comprehensive biography of Dorothy Miller, the groundbreaking curator who joined the Museum of Modern Art in its early years, building, over the course of decades, an innovative and remarkable program promoting contemporary American artists. Here, Jeffers recounts some key moments from this extraordinary life.

Michael Slenske pays tribute to the life and work of artist Ashley Bickerton.

Charles Stuckey reflects on the unparalleled life and career of the gallerist, patron, and curator Virginia Dwan, enumerating key moments from a lifetime dedicated to artists and their visions.

Michael Auping pays tribute to the late bicoastal curator, admiring her contributions to the proliferation of Conceptual art.

Carlos Valladares celebrates the visionary Brazilian director.

Aria Darcella pays homage to the founder of Details magazine, enumerating the many ways in which Flanders changed discourses around fashion, nightlife, and photography.

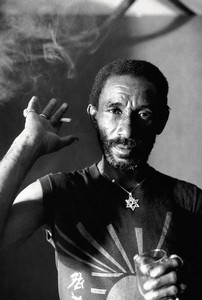

Connor Garel celebrates the outsized impact of this legendary musician on the world of music and beyond.