Reflecting on the tropics in his memoir Tristes Tropiques (1955), Claude Lévi-Strauss asserts that “history is only ever the superficial part of the iceberg. The essential truth lies elsewhere, in the depths of the mythological substratum.”1 Adriana Varejão’s exhibition at the Hispanic Society Museum, Don’t Forget, We Come From the Tropics, probes the layered histories and mythologies of the Amazon rainforest, inviting New Yorkers to engage with stories from the heart of the tropics and the lungs of the Earth. The title, drawn from a famous declaration by the Brazilian modernist Maria Martins, evokes Brazil’s ecological and cultural vitality while reflecting Varejão’s baroque sensibility—one mirroring the hybridity and excess of the tropics. Her new sculptural paintings and painted sculptural installation explore a convergence of artistic mediums, fine art and craft, humanity and nature, and history and myth, connecting us to the Amazon as a living, breathing repository of knowledge.

The exhibition premieres the latest additions to Varejão’s Pratos (Plates) series (2011–). Inspired by the delicately textured plates of the sixteenth-century French potter Bernard Palissy and the nineteenth-century Portuguese ceramicist Bordalo Pinheiro, Varejão’s Pratos set surreal and sensual depictions of nature, femininity, and birth on large fiberglass tondos with protruding three-dimensional elements hand-sculpted by the artist and painted in oil. The sculptural aspect of these paintings evokes the theatricality of Baroque architecture, where ornate sculptural reliefs break free from the surfaces of walls and ceilings to create an immersive sense of movement and drama. While Varejão’s previous Pratos delved into the ocean’s depths, these new works reflect her continued engagement with the Amazon rainforest, stemming from her participation in the inaugural Bienal das Amazônias in 2023 and marking two decades since she began her research in the region.

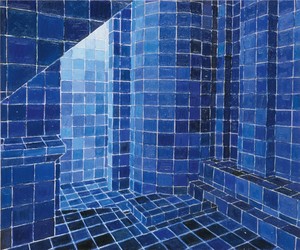

The Hispanic Society’s main gallery includes a Baroque-revival arcade of grand terra-cotta-colored archways. In response to this distinctive architecture, Varejão has installed her Pratos as freestanding sculptures within these archways, inviting us to move around them and appreciate their three-dimensionality and the contrasts between their two sides. On the front of each plate, exuberant imagery of Amazonian flora and fauna—including a mucura (Amazonian opossum), guarana (an Amazonian fruit resembling the human eye—“fruit like the eyes of the people”), botos (pink river dolphins), a matamata (river turtle), and an urutau (nocturnal bird)—highlight the seductive intricacies of nature. On the reverse, Varejão has painted designs adapted from historical ceramics in the collection of the Hispanic Society and beyond, including Spanish Valenciana, Ottoman Iznik ware, Ming dynasty Hongzhi porcelain, and pre-Columbian Amazonian Marajoara pottery. This simulation of artisanal styles traversing continents and millennia reflects an artistic process that is as baroque as it is anthropophagic—devouring and reimagining unexpected cultural encounters. The juxtaposition of the two sides of each plate—between natural and human-made patterns—encapsulates a tension between organic vitality and humanity’s desire to immortalize, offering an interplay between the moving, breathing organisms of the Amazon and the crafted, enduring patterns of human history.

When painting the animals in her latest Pratos, Varejão drew inspiration from the scientific drawings of the seventeenth-century Portuguese friar Cristóvão de Sá e Lisboa, who drew to document the findings of his expeditions in colonial Brazil. These early attempts to catalog the wonders of the Amazon reflect both humanity’s admiration for nature and its desire to control it. Now, they foreshadow the region’s destruction. The Amazonian species depicted in Varejão’s Pratos, many now endangered, are at once powerful and vulnerable, embodying the kind of fusion of opposites typical of the Baroque. Creatures such as vibrantly patterned poisonous dart frogs exemplify this paradox, combining vivid beauty with inherent toxicity, attraction with repulsion, and life with death. This harmony of extremes, central to the Baroque ethos, has always permeated Varejão’s work.

Expanding on the tensions between nature and humanity, Varejão’s monumental sculpture outside the museum on the Audubon Terrace activates the institution’s bronze statue of El Cid (1927) by Anna Hyatt Huntington. In Varejão’s site-specific work, a vibrantly painted fiberglass sucuri (an Amazonian anaconda) coils around the bronze warrior, subverting the statue’s symbolism of imperialism, masculinity, and human dominion over nature. In counterpoint to this equestrian figure’s demonstration of control over a domesticated animal, the presence of the snake introduces an unexpected collision between the tamed and the wild. Surrounded by the permanently inscribed names of historic conquistadors on the Audubon Terrace, the snake disrupts this colonial space and creates a confrontation between humankind and nature. Martins too made serpentine, anachronistically Baroque sculptures, and by referencing her in the exhibition’s title Varejão bridges her legacy and Huntington’s, two pioneering female sculptors from opposite hemispheres.

The embrace of the serpent in both Varejão’s outdoor sculpture and her Pratos invites reflection on the forces at work in the plight of the Amazon, where nature is both enduring and endangered. Across cultures, the serpent is an ancient symbol of rebirth, transformation, and the feminine divine. In Varejão’s Guaraná (2024) plate, three Amazonian boas slither around venomous dart frogs and a three-dimensional assemblage of ripe guarana fruit burgeoning from a deep-magenta background. The plate’s luminous surface, speckled with white flecks, evokes a cosmic void or a swirling nebula of stars. This imagery conjures the cosmic mythologies surrounding guarana, a surreal-looking fruit ubiquitous in Brazilian consumer culture as the inspiration behind the name and flavor of the country’s national soda. In the Amazon, guarana plays a role in the origin myth of the Sateré-Mawé people, one of the largest of Brazil’s 255 Indigenous groups. Recounted in Seth Garfield’s book Guaraná: How Brazil Embraced the World’s Most Caffeine-Rich Plant (2022), the myth describes a deity, Jurupari, who transforms into a serpent and kills a beloved young boy. After the tragedy, the boy’s mother transforms her pain into an act of creation, decreeing that his eyes be planted to grow a fruit capable of healing all ailments. From the tears of the tribe and the boy’s buried eyes sprouted the guarana plant, its red, eyelike berries symbolizing resurrection and healing. Today, the Sateré-Mawé people call themselves “the children of guarana.”2

The first work from this new body of Pratos, Mucura of 2023, debuted at the Bienal das Amazônias that year alongside Varejão’s multimedia installation Em Segredo (In secret, 2023). Em Segredo juxtaposes a colonial botanical illustration, in the upper part of a canvas that unrolls from the wall down onto the floor, with a painting of a banana leaf on which rests a sculpted fetus. Beneath the banana leaf is a text reading “Ya pihi irakema,” a Yanomami phrase that directly translates as “I’m contaminated” but is used to describe the transformative experience of falling in love—a phenomenon in which one’s body and mind are consumed by another person, rendering one vulnerable yet profoundly alive, much like the act of creation itself. As David Servan-Schreiber writes, “To say ‘I love you,’ the Yanomami say, ‘Ya pihi irakema,’ meaning ‘I have been contaminated by your being’—a part of you has entered me, and it lives and grows.”3

Mucura revisits these concepts of creation and the body. Within the verdant contours of the rainforest, light pierces a dense canopy of cascading vines, emitting a lush glow, as if the forest were alive with secrets. Emerging from within these vines is a silhouette of the artist’s own pregnant body, painted after an old photograph, merged with the head of a mucura, the Amazonian opossum. The mucura is among the most fertile mammals, capable of up to three pregnancies annually, and it is remarkably resistant to snake venom. A symbol of femininity, fertility, and resilience, these ancient marsupials embody survival and continuity in the world’s largest ecosystem.

In Urutau (2025), Varejão continues her exploration of Amazonian stories of the feminine divine by depicting the nocturnal bird the urutau, a name meaning “mother of the moon.” The haunting song of the urutau has inspired legends about women changing into these birds and singing to the moon after experiencing heartbreak. These stories have added weight through the significance of the moon: in Tupi mythology, it was the moon goddess Jaci who gave birth to the entire Amazon River and all the life it sustains. In Urutau, Varejão evokes a moonlit forest where the bird spreads its wings and looks down at us with a piercing, fiery gaze. The background is deep midnight blue marked by bright white brushstrokes, three-dimensional butterflies adorning eyelike patterns orbit the scene like celestial messengers, and the moon, positioned at the center of the plate, casts its silvery light, inviting reflection on nature’s quiet power and enduring mysteries.

Varejão’s new Pratos pay homage to an overlooked worldview in which women and nature are valued sources of creation, renewal, and resilience. In stark contrast, the relentless destruction of nature for profit, driven by male political leaders and corporate magnates, underscores the gendered power dynamics of our climate crisis. Through this lens, Varejão’s work draws attention to stories from the periphery that demonstrate reverence for the natural world and critique the dominant forces that imperil our planet. This perspective has been central to her practice since the 1990s, long before decolonial discourse was as prominent in the art world. When the Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa was organizing Varejão’s first retrospective, Histórias às margens (Histories at the margins) at the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo in 2012, he described the show’s title as referring to the “histories and stories often forgotten or relegated to the margins by historic tradition, irrespective of whether they refer to Brazil, Portugal, China, art itself, the Baroque, or colonization. Varejão researches these histories, and interweaves them in her paintings.”

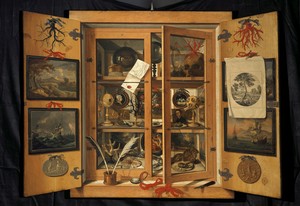

This spirit of inquiry continues in Varejão’s current exhibition, where she places her new works in dialogue with historical ceramic plates from the Hispanic Society’s collection. The museum, which holds over half a million objects from the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking world, contains thousands of ceramics from which Varejão has curated a selection of twenty. By situating these plates alongside her own monumental plate paintings, Varejão raises provocative questions about the hierarchies of aesthetics. Historically, ceramics have been relegated to the edges of museum collections and referred to as “craft” or “decorative arts,” secondary to painting and sculpture. In creating sculptural paintings inspired by ceramics, Varejão challenges these assumptions and raises the question, Why are certain forms of artistry considered artisanal rather than fine art, and who determines these distinctions? Her works blur these boundaries, demonstrating how ceramics, with their history in every culture, can engage with contemporary issues and enrich our understanding of art.

Through her sculptural paintings and painterly sculpture, Varejão challenges us to expand our understanding of art and craft, humanity and nature, and history and myth. She embraces the Amazon as a baroque body—an ever-growing rhizome with a multiplicity of histories and stories, much like the diverse organisms that flourish in the rainforest itself. By weaving the mythological substratum of the tropics into her art, Varejão centers the Amazon as a profound source of cultural depth, inviting us to take a closer look at its histories and to heed the knowledge and inspiration it can offer the world.