Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2023

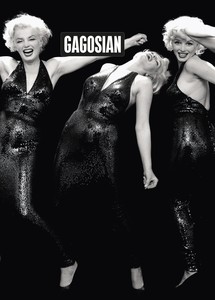

The Summer 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Richard Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957 on its cover.

Spring 2025 Issue

Last fall, Taryn Simon debuted an interactive sculpture entitled Kleroterion (2024). Based on a device from the beginnings of democracy in Athens, the work was installed at Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York. As part of that presentation, Simon participated in a panel discussion with Nora Lawrence, Tomás González Olavarría, and Philip Lindsay about democracy, sortition, and art’s place in politics.

Taryn Simon, Kleroterion, 2024 (detail), mixed media, 67 × 18 × 16 inches (170.2 × 45.7 × 40.6 cm), edition of 3 + 2 AP. Photo: Taryn Simon

Taryn Simon, Kleroterion, 2024 (detail), mixed media, 67 × 18 × 16 inches (170.2 × 45.7 × 40.6 cm), edition of 3 + 2 AP. Photo: Taryn Simon

Taryn Simon has imagined an election machine based on surviving archaeological fragments of a device known as a kleroterion, which was used at the beginnings of democracy in ancient Athens. To prevent corruption, all male citizens of the city had the opportunity to hold public office or sit on a jury through the unpredictable workings of a kleroterion, an instrument that used a lottery system to ensure randomized selection of a winner. The integrity of a transparent election process was preserved by placing the kleroterion in public areas where everyone could observe the proceedings.

Simon’s sculpture Kleroterion demonstrates how randomized outcomes can counteract authoritarian forces in groups ranging from a family through a community to a nation. What if questions such as “Who decides what’s for dinner?” and “Who decides if we go to war?” were determined by chance and the pull of a lever? The making of Kleroterion, and its installation at Storm King Art Center in New Windsor, New York, coincided with the presidential election season in the United States. Asking what might be lost or gained through a process of randomized resolution and inviting everyone to participate, the sculpture spotlights the ways in which decisions are made and the dynamics of both families and our political system.

Below is an excerpt from a panel discussion about Kleroterion at Storm King Art Center in November of last year. Along with the artist, the panelists were: Nora Lawrence, Executive Director, Storm King Art Center; Philip Lindsay, Democracy Innovations Program Manager, Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities, Bard College; and Tomás González Olavarría, founder of Tribu, a nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing innovations and institutional reforms to modernize democracy.

Nora LawrenceTaryn, what was the genesis of this work?

Taryn SimonThe piece started when I was in Athens researching ancient receipts, carved into stone, that preceded paper-and ink-records. I went to a museum holding ancient artifacts where I stumbled on a fragment of a kleroterion from the early days of democracy. There isn’t one preserved intact anywhere, so I started to imagine its forms.

NLAnd what was its purpose?

TSIt was designed to randomize the process of selecting citizens for positions of power, including public office and juries. All citizens—in ancient Athens that excluded women—were invited to throw their hat into the ring. It was an attempt to build a transparent lottery system. I wanted to take the crumbs of that “election machine,” let’s call it, and build them into a game.

NLI think it’s critical that we placed Kleroterion in an open space. Can you talk about the logic behind that?

TSIn early accounts of the kleroterion, it was always positioned in open space, sometimes on a hill, giving a 360-degree-view to all the participants or observers of the electoral proceedings. Circling the machine meant no hidden back door and less possibility for corruption.

NLPhilip, you were familiar with this history before seeing Taryn’s work; could you talk about the origins of the kleroterion?

Philip LindsayI’ve worked on a few political campaigns, and the reality is that working on elections is exhausting: it’s pretty much a winner-take-all system, and in the US it’s run in an industrial way that often leaves organizers burned out and the populace divided. Starting in 2021, we at the Hannah Arendt Center started to host conferences and trainings on sortition, which is the use of random selection to choose representative bodies. It’s an alternative to election in which we could instead select large bodies of people to come together and speak to each other across geographic and ideological lines to reach a decision on a subject. It sounds crazy but in fact it’s the original meaning of the word “democracy” in ancient Greece. There, the term democracy or “rule by the people” referred to the random selection of members of the political juries according to their demes, the Greek version of our counties. Your citizenship was tied to your deme.

This was a new system, invented around 400 to 500 BC. It was intended to break up the old clan- and wealth-based tribes in ancient Athens: the aim was to force people from the coast, from the mountains, from the inlands, to meet and talk and get to know each other, participate in art festivals together, travel together, fight wars together. It’s as if we in the modern US said, We’re going to break up the two-party system, we’re going to break up the urban/rural divide, we’re going to break up the old culture wars, and from now on, when you turn eighteen, you’re going to have to go on a service-based camping trip for a few months with someone from the other side of the aisle, the other side of the country.

Tomás González OlavarríaWithout a collective sense of identity among all members of a society—a shared “us”—democracy cannot truly function. This mutual recognition is essential for the social cohesion that underpins a stable society. In democratic innovations like sortition, modern societies—diverse in nature—have an opportunity to strengthen their social fabric and shared understanding.

The way we live together depends on culture, technology, and institutions. While cultures evolve and technologies advance rapidly, institutions often lag behind, creating a gap that leaves democracy struggling to keep pace with change. My work focuses on democratic innovations, aiming to remind us that the mechanisms implementing democratic ideals must evolve to stay true to their purpose. As the Chilean biologist and philosopher Humberto Maturana once said, “When we talk about change and innovation, the first thing we should ask ourselves is: what do we want to preserve?” In a rapidly changing world, preserving the essence of what we are—and what we want to be—requires embracing change. Because institutions are resistant to change, we must make deliberate efforts to adapt them continuously. This will ensure that they uphold their core values, deliver tangible results to improve living standards, and foster a society where we remain willing to live together. Taryn Simon’s artistic interpretation of the kleroterion communicates the principles of sortition and democratic ideals as a foundation for living together, inspiring broader audiences to imagine democratic innovations.

Taryn Simon, Kleroterion, 2024, installation view, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York. Photo: Eli Baden-Lasar

NLAnd that’s a key thing that we’ve been seeing in visitor interactions with Taryn’s Kleroterion: it opens up the types of things that we’re interested in deciding on or thinking about. So, for instance, a few of us were out by the work and a young child came up to it. He decided that what it would decide was who, among all of us there, would get to jump around in a circle. And that was very important to him, so we all jumped around in a circle with him when he actually did win. It can be a big decision, it can be a small decision, but the people coming to it have their own idea of what that might be.

TSAnd what the world could look like—a place where we could decide to just jump around in circles all day. That sense of gaming, of strategy and play, is at the sculpture’s heart. I’ve wanted to make a game for a long time. I grew up in my grandfather’s and father’s arcades; both of them invented, manufactured, and distributed old-school arcade games, air hockey tables, pool tables. Games were like oxygen, always there. The arcade has been a huge part of my life and influences how I see systems and people operate. And there’s no bigger game than politics.

We designed the kleroterion to be the color of a cue ball and the chips are the color of pool balls. As in pool, the balls move through unpredictably, bouncing off each other, driven by the motion of one individual.

NLThe machine has five chips, because you wanted the number of chips to match the size of an average family. Can you speak to your interest in highlighting decision-making at different scales?

TSSo much of the disruption, corruption, death drive, and folly we see on the big stage is found in a small group, in a family, even in an individual brain. The process of decision-making—what you’re going to eat for dinner, who gets to do what, who leads—operates through the same mathematics and chaos.

Taryn Simon, Kleroterion, 2024, installation view, Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York. Photo: Eli Baden-Lasar

NLTomás, could you speak a little bit about your work of putting a lottery-based system into practice in Chile?

TGOThe organization I lead, Fundación Tribu, spearheaded a public deliberation process in partnership with the Center for Deliberative Democracy at Stanford University, led by James Fishkin, creator of a methodology that has been implemented over 100 times worldwide in the past thirty years. Our project—the first deliberative-democracy process to use a nationally representative civic lottery in Latin America—was formally endorsed by the Chilean senate and supported by organizations such as the US Embassy, CNN Chile, the Universidad de Chile, and the Asociación Chilena de Municipalidades. It involved 514 people from all regions of Chile, selected through a random lottery to ensure maximum independence and representativeness. The group was statistically representative of Chilean voters with a margin of error below 5 percent. The process focused on concrete proposals of reform to the pension and health care systems. All these proposals had been developed over the past decade by technical experts from across the political spectrum and were presented to participants in a balanced manner, including arguments for and against each one. The results make notable contributions to address disinformation, lower polarization, increase civic literacy, and build consensus around policy issues.

While not yet a formal system, this mechanism holds significant potential to complement democracy as we know it. That first process helped to showcase how a randomly selected body could work, and now we’re looking forward to developing a roadmap of research, capacity-building, and institutional development to address the challenges and open questions in order to institutionalize this mechanism. Randomly selected groups can strengthen democracy by incorporating diverse perspectives, both technical and experiential, into public deliberation. They also promote civic education by actively involving citizens and help to align incentives in public decision-making, as participants have no political ambitions tied to their involvement.

NLHow does this piece function within the larger preoccupations or ideas in your practice as an artist, Taryn?

TSI keep making sculptures that people can be in or play with—things that can be touched and felt. Or sonic things that echo and crank. I guess after making so many two-dimensional objects that you observe—photographs, video—it became really important to make something that could be held.

NLOur conversation today reminds me of your earliest project, The Innocents [2000–03], where you were looking at criminal legal processes, jury selections, and even obliquely the history of sortition. The text about Kleroterion posits that the work “asks what might be lost or gained through a process of randomized resolution.” What do you see as benefits? How do you think about that statement?

TSThe tricky thing is that randomization is basically impossible and ultimately patterned or rigged in some way. But true randomization I guess could be a way to escape prescribed choices—a way to let the possibility of unknown, unexpected, and unresolved realities peek in.

Artwork © Taryn Simon

Taryn Simon, Gagosian, Park & 75, New York, March 20–April 26, 2025

Tomás González Olavarría is an economist, a fellow at the European University Institute, and the founder of Tribu, a nonprofit organization working to advance innovations and reforms in democracy. He led Latin America’s first national deliberative-democracy process.

Nora Lawrence is the executive director of Storm King Art Center, New Windsor, New York. Lawrence has played an integral role in raising the center’s profile, seeing its audience grow four-fold and bringing in a new generation of artists. In 2023 she cocurated a site-specific commission by the artist Martin Puryear there. Lawrence has developed nearly twenty exhibitions with Storm King’s curatorial team, working with artists including Lynda Benglis, Mark Dion, Rashid Johnson, and Wangechi Mutu.

Philip Lindsay leads the Democracy Innovation Hub at the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities at Bard College. Over the past three years, the Hub has hosted annual gatherings for advocates and practitioners of citizens’ assemblies in the United States. These gatherings led to the first major use of sortition in New York City, in 2023.

Born in New York, where she lives and works, Taryn Simon received a BA in semiotics from Brown University in 1997. In 2001 she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for what would become her first major photographic and textual work, The Innocents (2002), which was exhibited at MoMA PS1, New York. Incorporating mediums ranging from photography and sculpture to text, sound, and performance, each of her projects is shaped by years of rigorous research and planning, including obtaining access from institutions as varied as the US Department of Homeland Security and Playboy Enterprises, Inc.

The Summer 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Richard Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957 on its cover.

The Fall 2022 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Jordan Wolfson’s House with Face (2017) on its cover.

This spring, as part of the Lambert Family Lecture Series at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Taryn Simon joined Teju Cole for an online conversation about her artistic practice and creative process.

In Taryn Simon’s performance work An Occupation of Loss (2016), professional mourners enact rituals of grief, simultaneously broadcasting their lamentations from within a sculptural installation. This video by filmmaker Boris B. Bertram documents the April 2018 performance of this work with Artangel in Islington, London.

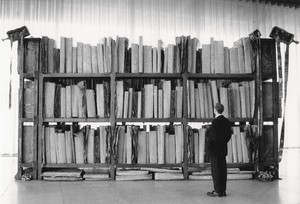

Joshua Chuang, the Robert B. Menschel Senior Curator of Photography at the New York Public Library, discusses the institution’s singular Picture Collection, the artist Taryn Simon’s rigorous engagement with it, and four instances of its little-known role in the history of art making.

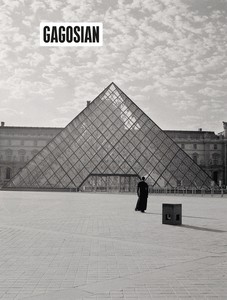

The Summer 2021 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Carrie Mae Weems’s The Louvre (2006) on its cover.

James Lawrence explores how contemporary artists have grappled with the subject of the library.

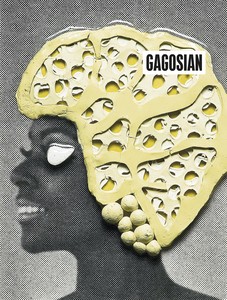

The Summer 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a detail from Afrylic by Ellen Gallagher on its cover.

Two immersive installations by Taryn Simon presented at MASS MoCA in 2018–19 examined the rituals of cold-water plunges and applause. Text by Angela Brown.

Meredith Mendelsohn discusses the impact of Free Arts NYC and its mission to foster creativity in children and teens, on the occasion of its twenty-year anniversary.

Taryn Simon’s 2016 exhibitions spanned the globe. Angela Brown brings us highlights from six museums.

On the eve of ECHOES FROM COPELAND, an exhibition of new paintings at Gagosian, New York, Nathaniel Mary Quinn met with Ashley Stewart Rödder to discuss the genesis of the works he’s been creating, their literary origins, and his evolving approach to the practices—and intersections—of painting and drawing.