Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Spring 2023

The Spring 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Roe Ethridge’s Two Kittens with Yarn Ball (2017–22) on its cover.

Spring 2023 Issue

Contemporary artists Adam McEwen and Jeremy Deller met up online over the holiday season to discuss McEwen’s upcoming exhibitions in London and Rome. McEwen delves into the motivations and criteria behind his work, as well as the challenges and complexities of memorializing the living.

Adam McEwen, Good Night, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 84 × 65 inches (213.4 × 165.1 cm). Photo: Rob McKeever

Adam McEwen, Good Night, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 84 × 65 inches (213.4 × 165.1 cm). Photo: Rob McKeever

Jeremy DellerYou have an exhibition coming up in London; what will you be showing?

Adam McEwenI’m showing a group of obituaries for living people. These are new works in a series that I started in 2000—I’ve taken around ten years off from making them so it’s been engaging to revisit the project.

JDWhy the hiatus?

AMHonestly, they’re quite stressful. For a while, I simply wasn’t drawn to any particular subject, and forcing something wouldn’t work.

JDWhen you say stress, why?

AMThe doing: the writing, the editing, the decision-making.

JDWhen you start, does a specific subject occur to you, or do you have a cast of characters you’re always thinking about as potentials? I imagine you have people telling you, Oh, you should do this person, you should do that person—is that helpful or does it feel like an interference? Because I’ve suggested people that you haven’t taken up, quite wisely [laughter].

AMSometimes people drift into my field of awareness, for any number of reasons, and I know they make a lot of sense. That said, people often make sense for a minute and then a week or a month later they don’t at all.

JDSo sometimes you’re probably very glad that you haven’t done an obituary quickly and shown it because that would have been a mistake. You have to ruminate for a while.

AMYes, I have to believe in it. I’ve done a few where history has moved on and the person’s own history has really changed afterward. I wrote an obituary of Aung San Suu Kyi from Myanmar; I’d been aware of her since I was a teenager because my dad knew her brother-in-law, so there was this sort of connection, and when I wrote the obituary she had won a Nobel Peace Prize, yet there was this underlying story and questions around her legacy that made it interesting. It seemed perfect. After I wrote it, everything fell apart over the course of the next couple of years and she’s now a very different figure.

Adam McEwen, Untitled (Greta), 2023, chromogenic print, dry mounted on Dibond, 60 × 40 inches (152.4 × 101.6 cm). Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

JDWhat are the criteria, then?

AMIt’s not totally consistent, but generally it’s a combination of homage, admiration, and interest. There must be a narrative there, a progression. At the same time, there’s usually a sense that they’re not in control of the story. So it’s not as simple as “I think this person is great.” Let’s say I think Stevie Wonder is great, a genius. But with Stevie Wonder there isn’t a counterstory; we’re all on the same page, in agreeing that he’s a genius. Whereas, with someone like Bill Clinton it’s more complex.

JDAbsolutely. He’s a flawed character.

AMThat’s right, but not all of them are what I’d call flawed, it’s just that they have some struggle around their persona. When I did Nicole Kidman, she seemed to be the only actress who in 2004 fit that old-school Hollywood-icon archetype, but then you see interviews with her on television, speaking about her marriage to Tom Cruise and this whole backstory of conflict—there’s a disconnect between what she’s presenting and what we’re seeing. That disconnect is crucial.

JDIt’s interesting because you’re memorializing people before they’re dead, which ties into conversations around public memorials and monuments that have been playing out all over the world. In the UK there have been buildings named after people like Aung San Suu Kyi, because she was seen as a great civil rights champion, but now there are movements to take those down.

AMExactly, scrub her out, Photoshop it.

JDBut now she’s on to the next act, where she’s in prison. So she’s going through this huge vacillation of highs and lows in terms of public perception. Do you ever get superstitious about creating these? Like you might be jinxing someone by indicating their death with the obituary?

AMNo, that doesn’t concern me. Most obituaries are prewritten, in any case: every big newspaper has filing cabinets with these texts already prepared. I’m simply opening the filing cabinet and taking out this object. I’m appropriating an already existing situation. More than anything superstitious, the anxieties lie in the responsibility inherent in consolidating someone’s life into a summary, which the form necessitates. You’re memorializing somebody, yes, but you’re essentially writing history. A journalist writes someone’s obituary in the afternoon, and the next day it gets read by a readership of a million or so in the Telegraph. And that then becomes a reference point. What they’ve written in a hurry becomes the material for scholars, biographers, and so forth. Whoever has the voice has the power to dictate the terms of history, which is strange and can be overwhelming.

Adam McEwen, Materiel, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 84 × 65 inches (213.4 × 165.1 cm). Photo: Rob McKeever

JDAnd in many cases, when you read obituaries, you’re encountering people you’ve never heard of before. The first and last time you’ll ever read or know about this person is their obituary. They get a half page, a quarter page, and that’s it. That’s their moment of glory. And those are actually the more interesting ones, reading about unknown figures’ lives—maybe they worked for the secret service, went into the oil-exploration industry, were in a coup in Nigeria or something. You read these amazing life stories of people who lived in the shadows.

AMExactly, and you’re like, How on earth can this amazing life have happened and I didn’t know anything about it? The more famous the person, the less likely the obituary will have anything you haven’t heard, because there’s so much to write about a famous person that “needs,” in inverted commas, to be included. They’re generally much more bland.

JDWhy do you choose celebrities, then, for your obituaries?

AMThey’re not at all about celebrity, although it looks like they are. The only reason to use a celebrity, from my point of view, is that if the viewer knows that person, because they’re well-known and they’re still alive, then in that split second when the viewer steps up and sees the work, there’s a strange moment of uncertainty. Like, Is Bill Clinton dead? I think that’s interesting because that weird little moment is as if the floor suddenly becomes unsteady. This is what I hope art can do.

JDUnsettling.

AMNot so much unsettling—

JDOr reality is run at a slight shift.

AMIn a sense, yes. And that’s really the only reason for the celebrities. I’ve often thought about doing obituaries of unknown people, in fact I can think of a couple of people I’d like to do that with, but it would become an entirely different project. I mean, the other thing about these is, everyone’s going to die. So these works have a built-in sell-by date. I know that the thing I’m doing is going to happen in real life—an obituary very much like the obituary I write is going to be published at some point in the future. When that happens—and I don’t want it to happen, but it will—the artwork becomes irrelevant and redundant. I thought that was funny. There’s this little ticking clock that will eventually run out, at which point you could just trash the artwork.

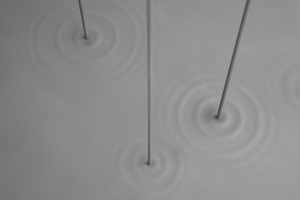

Adam McEwen, Rain Puddle, 2023, milled aluminum, 47 ¼ × 31 ½ × 2 ¾ inches (120 × 80 × 7 cm) © Adam McEwen. Photo: Lucy Dawkins

Adam McEwen, Rain Puddle, 2023 (detail), milled aluminum, 47 ¼ × 31 ½ × 2 ¾ inches (120 × 80 × 7 cm) © Adam McEwen. Photo: Lucy Dawkins

JDIt’s good that you didn’t do too many because you would just have been known as the obituary guy. You could have done them on commission.

AMPeople have asked to do them many times, but, again, I must be genuinely interested in the subject. People would say, Why don’t you write George W. Bush’s obituary? He’s a . . . you know. And it’s like, Why would I want to give my life and time to that? This is really an act of love.

JDIt comes from a good place, as they say [laughter]. You’re doing it for the right reason.

AMThere’s a sort of sardonic, amused side to it as well, of course. The first one I made was Malcolm McLaren, for a group show that [London art dealer] Paul Stolper curated. Everybody was given a muslin Vivienne Westwood remake shirt as their starting material and I printed the McLaren obituary on there. I met him, actually, and told him about this; he stopped for a second and then had a big laugh. I don’t know if it’s humor, exactly, but there’s a sort of wry—

JDThere’s something very punk about it as well.

AMRight, and it spoke to the way punk slides over to Andy Warhol. I wrote an obituary of the adult film actress Marilyn Chambers. Behind the Green Door [1972] was the first porn film I ever saw—one of my sister’s boyfriends bought the VHS tape one holiday when I was thirteen. To have a good reason to make an artwork that had an image of a woman and to call it Marilyn was just a way for me to say to myself how much I love the paintings of Warhol. So in a way, that kind of pleasure is also part of it. It’s like being able to notate things you love in making it.

JDIt’s interesting that you talk about Warhol. Although this series is very different from your other work in many ways, it’s massively related as well, since much of your work partakes in a dark Pop sensibility. If we’re thinking of Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein, what they were able to do so well was take a ubiquitous object, something we take for granted, something mass produced, and delineate its inherent beauty. I think you’re doing something similar. Is that fair to say?

AMCompletely. With the obituaries I’m taking a celebrity, a beautiful mass-produced object, one I don’t really understand myself, and redirecting attention to it. It works in a similar way to my sculpture in graphite, that process of feeling around in the dark to find objects that work. Maybe a watercooler is the same as Marilyn Chambers, in the sense of, you take them for granted, you have this relationship to them that many other people have also, and it’s hiding in plain sight. Your relationship is both straightforward and mysterious.

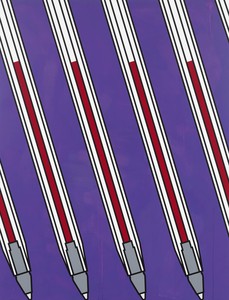

Adam McEwen, Kling Klang, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 84 × 65 inches (213.4 × 165.1 cm). Photo: Rob McKeever

JDRight, and what could be more ubiquitous than a Bic pen? You’re working on more of your Bic paintings for an exhibition in Rome, right?

AMYes. I’ve had the Bics as an idea for probably ten years. I took photographs of them and I kept them in the computer and I was like, I don’t know what that is, I really don’t. But I knew that Bic Cristals, the clear ones with a medium point, were somehow special objects. It’s a numinous object, it’s got an aura to it, this simplicity and this democratic ethos. And yet it’s just kicking around desks all around the world and not really revealing that.

JDI have ten of them within five feet of me now. The Bic paintings are also quite arresting because in some of them they look very aggressive, like missiles, and in others they look like legs. All of these paintings have their personalities.

AMThey’re a bit heraldic.

JDYes, potentially fascistic even?

AMYes, that’s right.

JDThey have a life.

AMAnd that only revealed itself when I made them at this size. Suddenly they seemed to relate to human scale. For Rome, I decided to only show Bic works on the wall. I want to keep it simple and just use that motif, instead of constantly trying. . . . I think there’s a thing that happens when one feels that one’s ideas aren’t good enough, so one shows as many ideas as possible at once. I’ve been guilty of this in the past, but this time I decided to just stay on that point—

JDNo pun intended.

AMYes, exactly, on that fine point, black ink, like this one in my hand [laughter]. You know what’s weird is that when I wrote obituaries, as a job, long before the artworks, I was assigned to write the obituary of Baron Marcel Bich, who bought the patent for what would become the Bic Cristal, which had been invented by the Argentinian László Bíró. It’s incredible how things come around. And I find the only good thing about getting to be incredibly old, as we are, is that you find that things you dismissed twenty-five years ago will later on prove to be pertinent. They feed work now.

JDThe circle is squared.

AMI had ideas when we first met, which was a very long time ago, and I was trying hard to make anything, but some of the ideas that I did not make then now make complete sense next to things that I want to make now. One isn’t necessarily wasting time by daydreaming, as it were.

JDIs there humor in this work as well?

AMNot always. A lot of people have a problem with humor; there’s a contingency that says humor in art is a symptom of that art’s failure. I don’t agree; I think humor is part of the equation. I don’t go out of my way to make humorous art but I think humor is a glue that can hold together opposing ideas.

JDBut the obituaries are mischievous, aren’t they?

AMThey lay themselves open to it, certainly. I have a photograph of Jeff Koons standing in front of his obituary: he’s smiling, and it’s a very funny photo. Or somebody told me that they went to the Whitney Museum [of American Art, New York] and saw, God bless her, Monica Lewinsky reading Bill Clinton’s obituary. That was reported on Gawker at the time; it’s hard to imagine a more humorous and loaded situation. But again, I don’t intend for them to be funny or to act in this way.

Adam McEwen, Untitled (Marc), 2023, chromogenic print, dry mounted on Dibond, 60 × 40 inches (152.4 × 101.6 cm). Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

JDIt’s the classic thing that you make an artwork and it goes out into the world and you have no control over how it’s seen or who sees it. You’re releasing it and just seeing what havoc it creates.

AMAnd as you know, you’re very good at that, it’s quite difficult to set out with the intention of creating havoc and succeeding. More often, it’s this unexpected consequence of something made with different intentions. But I remember at the beginning when I first showed these, in 2004, I did think, Is this really okay to do this? Is this a weird . . . ? And as much as it was an uncomfortable feeling, I search for that same feeling now. You want that feeling because that feeling of being uncomfortable is a good sign.

JDAre you working on any sculpture at the moment?

AMI’m in the middle of a new piece that will be shown in London with the obituaries. It’s a rain puddle, milled from aluminum to look like the surface of a puddle in spitting rain, with ripples and rods—

JDWith the rain landing?

AMVertical rods meeting the center of each ripple indicating the rain, yeah. The more I think about this work, there’s some relationship to the obituaries that I don’t really understand. Hopefully they’ll look good in the same room.

JDSomething about the passing of time and mortality, but also you’re making a sculpture of something that’s in a sense impossible to re-create as well. It seems like an impossible sculpture, effectively.

AMI hope it isn’t. I think in the back of my mind, it came from looking at Japanese woodcuts. I’m in awe of the way rain is handled in those; they figured out how to impart the feeling of being in the rain, but with such simplicity. I feel like that’s a goal. Maybe the art that we really like is the art that has as much removed from it as possible.

Adam McEwen, Gagosian, Davies Street, London, January 26–March 18, 2023

Adam McEwen: XXIII, Gagosian, Rome, February 10–April 22, 2023

Artwork © Adam McEwen

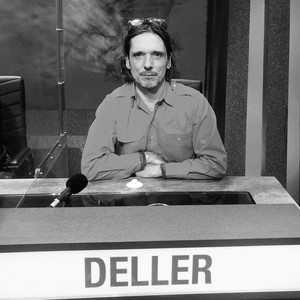

Jeremy Deller studied art history at the Courtauld Institute. Deller won the Turner Prize in 2004 and represented Britain in the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013. He has been producing projects since the mid-1990s, often in the public realm.

Adam McEwen was born in 1965 in London, England. He received his BA in 1987 from Christ Church, Oxford, and then received his BFA in 1991 from the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia. His multifarious practice includes obituaries of living subjects such as Bill Clinton, Greta Thunberg, and Grace Jones, alongside sculptures in various media and paintings on canvas and sponge. McEwen currently lives and works in New York City. Photo: Andisheh Avini

The Spring 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Roe Ethridge’s Two Kittens with Yarn Ball (2017–22) on its cover.

In conjunction with his exhibitions Adam McEwen at Gagosian in London, and Adam McEwen: XXIII at Gagosian in Rome, the artist sits down with author Ian Penman to discuss his new obituary works and graphite sculptures.

On the eve of ECHOES FROM COPELAND, an exhibition of new paintings at Gagosian, New York, Nathaniel Mary Quinn met with Ashley Stewart Rödder to discuss the genesis of the works he’s been creating, their literary origins, and his evolving approach to the practices—and intersections—of painting and drawing.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas spoke with artist, writer, and podcaster Joshua Citarella inside Kulendran Thomas’s exhibition Peace Core at Gagosian, Park & 75, New York. The pair discussed the makings and meanings of the exhibition, which juxtaposed a video work of infinite duration that continually remixes and reedits American television footage from the morning of September 11, 2001, with six expressionistic paintings based on AI-generated images depicting a largely undocumented massacre in Sri Lanka in 2009, perpetrated in the wake of the “war on terror.”

Ahead of her exhibition over the summer at the National Portrait Gallery, London, Jenny Saville met with the novelist Douglas Stuart to discuss Glasgow, the beauty and blemishes of bodies, and their respective creative processes.

Maximiliane Leuschner speaks with South Africa’s most-sought-after emerging choreographer, Mthuthuzeli November.

The celebrated New York School poet and Pulitzer Prize–winner James Schuyler is the subject of Nathan Kernan’s new biography, A Day Like Any Other: The Life of James Schuyler. Kernan narrates the wild turns in the poet’s life with great skill, from his peripatetic youth, through his years in the influential circle of W. H. Auden, on to his critical friendships with poets and artists such as John Ashbery, Jane Freilicher, Frank O’Hara, and Fairfield Porter. Here Raymond Foye, a friend of Schuyler’s (and the poet’s literary executor), talks with Kernan about the genesis of the project and some of the breakthroughs and challenges he encountered in its construction.

In this ongoing series the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist has devised a set of thirty-seven questions that invite artists, authors, musicians, and other visionaries to address key elements of their lives and creative practices. Respondents select from the larger questionnaire and reply in as many or as few words as they desire. For the third installment of 2025, we are honored to present Marina Tabassum, the architect behind this year’s Serpentine Pavilion in London, A Capsule in Time.

A dedicated gardener and writer, Olivia Laing has authored two books on the subject: The Garden Against Time and A Garden Manifesto. Here, Salomé Gómez-Upegui speaks with Laing about the wisdom they’ve gained from working on these books and how writing has shaped their understanding of the ever-evolving relationship between gardens and the art world.

Tory Burch, chairman and chief creative officer at her namesake brand, which she launched in 2004, met with the Quarterly’s Derek C. Blasberg this past June. The two discussed Burch’s Fall/Winter 2025 runway show at the Museum of Modern Art, her collaboration with Rashid Johnson and Janicza Bravo for the 2025 Met Gala, early encounters with art and its lasting effects on her process, and the ethical core of her approach to good business.

Carlos Valladares talks with filmmaker Abel Ferrara about Turn in the Wound, Ferrara’s recent documentary exploring the experience of art and the war in Ukraine.

For Art Basel 2025, the fair has commissioned Katharina Grosse to create CHOIR, a large-scale, site-responsive painting for the Messeplatz Project. The curator for the project, Natalia Grabowska, met with Grosse in her studio in Berlin ahead of the work’s creation to talk through the process; Grosse’s approach to the specifics of the Messeplatz’s architecture; and the importance of unscripted encounters.