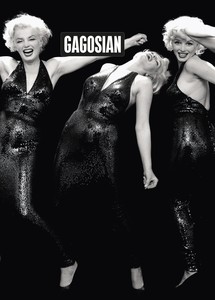

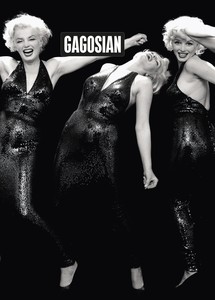

Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2023

The Summer 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Richard Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957 on its cover.

Fall 2024 Issue

Novelist Francine Prose visited Harold Ancart’s Brooklyn studio this past spring. Here, she reports on the paintings she encountered there and ponders the medium’s power to take us outside of ourselves.

Harold Ancart in his studio, Brooklyn, New York, 2024. Photo: Dianna Agron

Harold Ancart in his studio, Brooklyn, New York, 2024. Photo: Dianna Agron

It’s easy to lose yourself in one of Harold Ancart’s paintings. They’re disorienting, in all the ways in which you want art to alter your perceptions and orientation. An Ancart landscape draws you in, though it’s not like any landscape you know, or have imagined, or have seen on a wall. And is it even a landscape? It’s an invitation to travel to a world made entirely of paint marks on a canvas.

The mood of these works is dreamlike, spanning the wide range of moods and information that a dream can provide. But it’s not a dream you’ve ever had, nor, we suspect, is it the artist’s dream. Signposts help us get our bearings—water, earth, sky, horizon, plants—but these elements can appear in unexpected locations or combinations, and sometimes all alone. And what exactly are we looking at when we see that tree growing up in the middle of a canvas? Is it a cypress, or a mountain peak cloaked in vegetation, or a stationary ghost of the trees that caught Van Gogh’s eye in Arles? We more or less recognize a flower or plant, but we never imagined that it existed in such a wild range of crazy colors! The bright orange furry lollipop tree takes us back to the first time we experienced the marvel of the leaves turning in autumn.

Blossoms scattered across a network of branches evoke the giddiness of spring and at the same time the austere simplicity of Japanese art. Ancart, who is Belgian, has traveled to (and written a book about) Japan, and has clearly looked at a lot of ukiyo-e prints. The range of his sources, inspirations, and influences is subtle and broad. There’s a shimmer of Monet, a nod to Cezanne. When the landscape (rocky cliffs, shore, orange sun) is compressed to fit within the confines of a perfect circle, it’s a tip of the hat to the Tintin comics, of which Ancart is a lifelong fan. What we see in that circle is (Ancart laughs when he says this) what a pirate captain in Tintin sees when he scans the horizon through his spyglass.

The word “destiny” doesn’t appear often in Ancart’s vocabulary, but you sense that he believes in it. He understands that the art he wanted to make—the art that wanted him to make it—took him out of Brussels, where he grew up, and where his father was a dealer in antiquities. It steered him to art school (a pursuit that his family considered impractical) and helped him resist the trends of the era—a time when young artists were being encouraged to make work that was minimal, cerebral, and conceptual. Art brought him to New York, where, after lean years and rough patches, he has continued to thrive.

Harold Ancart, Deux Arbres, 2024, oil stick and pencil on canvas, in artist’s frame, 101 × 139 × 3 inches (256.5 × 353.1 × 7.6 cm)

In conversation, Ancart—a tall, friendly, voluble, energetic man in his mid-forties—keeps tracking back to the thing that artists understand, the open secret that keeps them grabbing the pen, or the camera, or, in Ancart’s case, the oil-paint stick. For all I know, some artists may look at a blank canvas or page and see little videos of themselves getting the Nobel Prize. But Ancart is talking about something else, something different, something that seems very familiar to me: the moment when you become so involved in your work that it’s as if you are no longer there. The ego ceases to exist. The work is no longer about you—the person who has disappeared into your work.

“Time vanishes,” Ancart says. “Time collapses. Things start flowing, You’re in the zone.”

It’s an exalted and precious state. “The work is telling you what to do. You make a mark and somehow you know what the next one needs to be.”

There’s a great Philip Guston quote that I am always quoting and probably misquoting, about how, when you—the artist—go into the studio to work, there are all these people and voices in your head: your wife, kids, dealer, critics, audience, et cetera. As you work, those presences leave the room, one by one, until finally, if you’re really working, you leave the room.

I’ve always thought of that state as taking dictation from a character who starts to speak in my mind, but for Ancart to reach that zone of guidedness and self-obliteration, the marching orders seem to come at least partly from color. Concerning that moment when the will disappears and something more mystical occurs, I think Ancart would say that it’s color, telling him what to do. His work reminds us of how many moods color can convey—mystery, solemnity, joy, fear. Color makes things new. You might think red flowers had been claimed—by Van Gogh, Matisse, more recently Andy Warhol—but Ancart’s red creates a new species of flower: unreal, surreal, essential. More jungly than the poppy, more like coral, or roses gone rogue. And there, under a Venetian sky, is a verdant patch of landscape not unlike the slivers of bluegreen countryside we glimpse beyond the window in a Netherlandish Annunciation.

Harold Ancart, Le Grand Parc, 2024, oil stick and pencil on canvas, in artist’s frame, 101 × 139 × 3 inches (256.5 × 353.1 × 7.6 cm)

In another large painting the mood is at once apocalyptic and festive. Pillars reflected in water multiply the divisions between light and darkness. The way everything hovers on the border of celebration and doom, stasis and storm, suggests an improbable but interesting conversation between John Singer Sargent and Lars von Trier. The painting shares with the rest of Ancart’s work the virtue of making you keep looking, as if something could be figured out, even though you know that what you want is the strangeness, the ambiguity, the casual but steady resistance to the rational and explicable.

Working in a large industrial loft, a former metal-storage warehouse smack in the middle of Bushwick’s exuberantly tagged metal doors and honking double-parked trucks, Ancart has created his own natural world, though he would need to walk quite a ways to see an actual living tree. It doesn’t seem to matter. It doesn’t matter. When Ancart is painting he might be anywhere. He’s in the painting. The zone. On one canvas, a small spray of poppies blooms—insisting on its right to exist—beside a bare whitewashed wall with darkened windows. Nature coexists with an unfamiliar space, as it does in the studio.

His show, which will be up in Paris from October 14 to December 20, is titled Maison Ancart. On the day I visited, many of the paintings for it were hanging in the studio. Underneath these works is a love for French landscape. Ancart talks eloquently about the moment when he fully got the true genius of Cezanne. His take on the natural world can bring to mind the hyperactive foliage of the Douanier Rousseau, or something more sun drenched, like Richard Diebenkorn, or Ellsworth Kelly’s gorgeous drawings of plants.

Harold Ancart’s studio, Brooklyn, New York, 2024. Photo: Dianna Agron

You can see art history in these paintings, but they aren’t like any others. Who knows how Cezanne would have painted if he’d watched a lot of films? Some of Ancart’s landscapes can look like sets for movies that will never be made. Maybe it’s his references to “the zone” that make me think of the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, the moody, slightly smudged, semi-hallucinatory way in which one image flows into another, the settings that combine memory and fantasy, desolation and overgrowth.

Ancart likes the idea that his oil-paint sticks—with which he works exclusively—have a mind of their own. It’s as if the medium had the power to turn the hand of the artist into something like a planchette moving over the Ouija board. He talks about paint sticks almost like collaborators, steering him from point to point. He lists the medium’s advantages: directness, immediacy, physical force, a pressure toward the abstract, rather than toward the microdetail that the tiny brush lives for.

Paint sticks encourage the accidents that aren’t accidental but suggestions, directions, provocations to do something unplanned and unexpected. Every mark (and the process of marking) is consequential. Possibly paint sticks provide the most immediate shortcut to a memory Ancart describes: his first childhood experience of drawing, of grabbing a pencil or crayon and seeing something or someone materialize on paper. The paint stick is the closest of any medium (except for pencil and finger paint, I guess) that connects the artist to that first burst of joy in color and form—the magic of the primal crayon. I’ve heard several artists say, as Ancart does, that they can remember how it felt the first time they drew something and knew: This is it. They were hooked.

Harold Ancart, La Montagne, 2024, oil stick and pencil on canvas, in artist’s frame, 101 × 139 × 3 inches (256.5 × 353.1 × 7.6 cm)

Harold Ancart in his studio, Brooklyn, New York, 2024. Photo: Dianna Agron

Twice during our relatively brief visit, Ancart brings up what seems to have been a formative moment, the end of a prelapsarian innocence in which he hadn’t heard that there was a right and a wrong way to draw, a correct and incorrect way to represent the figure. Someone pedantic and annoyed—a parent? a teacher?—reprimanded him: A hand has five fingers! Each time Ancart tells the story, you can watch him reliving the surprise of being told that you had to get things right. You couldn’t just make up the number of digits. A hand has five fingers! (Presumably, the adult had never looked too closely at Mickey and Minnie Mouse.) You can’t help thinking about how much of Ancart’s work has been a response. Let’s pick up the paint stick and make that first mark—and then let’s see how many fingers the hand is going to have. You can imagine Ancart following his oil sticks back to an Eden so sublime that the imaginary garden takes over everything else.

I began by talking about disappearance, and I want to end with it. One of the things that’s so remarkable about painting—that is, about the paintings we love—is that they let us leave our minds and bodies and enter the world of the painting. I once mysteriously lost two entire hours in front of Bosch’s Temptation of Saint Anthony in a museum in Lisbon. I remember, when I was a child, believing that the border between the two- and the three-dimensional was narrower and more porous than I think it is now. I remember a book on Sienese painting I found in our attic; I believed that concentrated contemplation—staring—could teleport me inside those towns and castles, those crenellated pink and lime-green walls.

Being in Ancart’s studio made me think how remarkable it is that the experience of the artist—the sense of vanishing, of disappearing into the work—can, in a very different form, be reproduced in the viewer. You’re in a contemporary art space in Brooklyn—and then you’re somewhere else, submerged in a boggy landscape, staring up at craggy mountains, moving closer for a better look at those improbably dark trees.

Artwork © Harold Ancart

Harold Ancart: Maison Ancart, Gagosian, rue de Ponthieu, Paris, October 14–December 20, 2024

Francine Prose’s most recent novel is The Vixen (2022). Her other books include Caravaggio: Painter of Miracles, Peggy Guggenheim: The Shock of the Modern, Reading Like a Writer, and Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932. The recipient of numerous grants and awards, she often writes about art. She is a distinguished-writer-in-residence at Bard College.

The Summer 2023 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Richard Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe, actor, New York, May 6, 1957 on its cover.

Harold Ancart speaks with novelist Andrew Winer about being present, finding freedom in tension, and pathological escapism.

Jordan Carter, curator and cohead of the curatorial department at Dia Art Foundation, New York, engages with the new artist’s book Cady Noland: Polaroids 1986–2024.

Carlos Valladares tracks the artist’s engagements with Hollywood glamour, thinking through the ways in which the star system and its marketing engine informed his work.

Miriam Bale reports from Cannes on the 2025 edition of the international film festival, highlighting three standout films.

Harry Thorne addresses the practical and conceptual links between the visual art of Peter Doig and the work of various musicians on the occasion of Peter Doig: House of Music at Serpentine, London, an exhibition opening on October 10, 2025.

Anna Weyant’s first solo institutional exhibition, at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, was curated by Guillermo Solana in close collaboration with the artist, and places more than twenty paintings by Weyant in dialogue with a selection of works from the museum’s permanent collection. Sydney Stutterheim considers the artist’s contemporary exploration of suspense, identity, concealment, and temporality.

Brian Dillon celebrates the sonic revolutions initiated by Beach Boy Brian Wilson.

Tracking works by Chris Burden, Bruce Nauman, Maria Nordman, and Eric Orr as outliers and outcroppings of the California Light and Space movement, Michael Auping argues that darkness—the absence of light and space—is a key element of the aesthetic.

The jewelry designer Jean Schlumberger permanently changed the face of High Jewelry with his daring approach to materials and techniques. His engagement with flora and fauna from the sea to the sky, and his choice of unparalleled gems, found an eager audience during his lifetime and continues to glamour the eyes and minds of jewelry lovers today. The Quarterly’s Wyatt Allgeier explores his life, legacy, and the persistence of his studied yet whimsical work.

The Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916) has been on Ed Ruscha’s mind as he creates a new body of work for an exhibition at Gagosian, Paris, this October. Christian House visits Copenhagen to consider the quiet and persistent power of Hammershøi’s art.

A major retrospective of the work of the Colombian fiber artist Olga de Amaral has landed in Miami by way of Paris. Presented in collaboration with the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, this career-spanning exhibition will be on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, through the fall of 2025. Here, Ekaterina Juskowski delves into the six decades of Amaral’s life, work, and inspirations.