Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2025

The Summer 2025 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Pablo Picasso’s Nu accoudé (1961) on the cover.

Spring 2019 Issue

Michael Cary pays homage to the visionary dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884–1979).

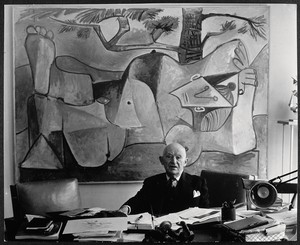

Brassaï, Kahnweiler in his office on rue Monceau, before a painting by Picasso, 1962

Brassaï, Kahnweiler in his office on rue Monceau, before a painting by Picasso, 1962

It is great artists who make great dealers.

—D. H. Kahnweiler

In September of 1908, a twenty-six-year-old painter named Georges Braque submitted six paintings to the Salon d’Automne. They were promptly rejected by a jury whose members included Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault. (Even in an avant-garde, there are guards at the gate.) Braque’s response was to take the canvases to an enterprising young dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who took a prompt action of his own: the day after the Salon closed, he opened Braque’s first solo show, an exhibition of twenty-seven works. Reviewing the show in Gil Blas, critic Louis Vauxcelles wrote that Braque “reduces everything—places and figures and houses—to geometrical patterns, to cubes.” The market for Cubism was born.1

Kahnweiler had been primed for the shock of Cubism by his visit to Pablo Picasso’s studio the year before. In the ramshackle Bateau-Lavoir building in Montmartre, Kahnweiler found Picasso isolated and depressed. The largest composition the artist had attempted to date had gone in a direction his friends couldn’t follow; their reactions had been universally sarcastic and discouraging, to the point of thinking that he’d gone mad and that this “Assyrian” style of painting would be the end of him. When Kahnweiler laid eyes on Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, however, he was stunned and dazzled. He “had the sudden intuition that a whole tradition had been overthrown as of that moment,” and the enthusiasm with which he tried to understand Picasso’s painting gave the artist a glimpse of a safe intellectual harbor.2 Meeting Picasso and seeing the Demoiselles changed Kahnweiler’s life—and the fact that he returned the following day to buy several gouaches and small paintings changed the artist’s as well.

Through his choices of which Cubists to exhibit and which to decline, Kahnweiler virtually defined the movement.

Kahnweiler was born to a prosperous banking family in Mannheim, Germany, in 1884. His work as a stockbroker in the family firm brought him to Paris, where he would make daily visits to the Louvre, a short walk from the Bourse. He fell in love with studying in person the paintings he had only ever seen in books, began collecting, and opened his first gallery, at 28 rue Vignon, in the spring of 1907. Kahnweiler embraced art as an adventure; he sought out the most challenging artists—and the most ridiculed—from the very start, with an interest in the Fauves Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain, and Braque. But it was his recognition of the cataclysm of Cubism that cemented his reputation.

Through his choices of which Cubists to exhibit and which to decline, Kahnweiler virtually defined the movement, and he signed exclusivity contracts with the four originators: Braque, Picasso, Juan Gris, and Fernand Léger. Armed with two Spaniards and two Frenchmen, this German dealer worked quickly to evangelize the Cubist revolution internationally. He courted the Russian collector Sergei Shchukin, the Swiss Hermann Rupf, and the Czech Vincenc Kramář, and he partnered with Alfred Flechtheim in Düsseldorf, the Thannhausers in Munich, and Alfred Stieglitz and the Washington Square Gallery in New York. His contracts protected his desire to be the sole conduit bringing the Cubists to market, but he also saw these agreements as gestures of an absolute faith and an effort to protect the artists from financial worries. He maintained that role until 1914.

At the outbreak of World War I, Paris was not the safest place for a German national. Kahnweiler was declared an enemy of the state, and his gallery and its contents were sequestered by the French government. He lost everything and spent the remainder of the war in neutral Switzerland, writing critical essays on Cubism and composing Der Weg zum Kubismus (The Rise of Cubism), his book-length study of the movement, which was published in 1920. He also returned to Paris that year, and opened a new gallery with a French partner (Galerie Simon, 29 rue d’Astorg), but was unable to reclaim his confiscated stock. The French government dispersed Kahnweiler’s holdings, including over 1,200 canvases by Braque, Picasso, Gris, and Léger, at rock-bottom prices, flooding the market in a series of humiliating auctions held between 1921 and 1923. Kahnweiler would suffer further when, in 1941, he found himself in danger once again, this time for being Jewish during the Nazi occupation of Paris. He successfully “Aryanized” the firm by transferring ownership to his stepdaughter, Louise Leiris, before waiting out the remainder of the war in the South of France. He returned to the “Galerie Louise Leiris” after the war and worked side-by-side with Louise until his death, in 1979.

Although most of Kahnweiler’s artists abandoned him out of necessity during World War I, he had a rapprochement with Picasso and became, again, the artist’s primary dealer later in life. The two men couldn’t have been more temperamentally different, yet the passionate, bohemian Spaniard and the grave and serious German businessman had formed a close bond at a crucial time in each other’s lives and a critical one in art history. Kahnweiler “liked smiling but disliked laughing,” another dealer, Heinz Berggruen, would remember, “but he was one of those art dealers who do not rely on charm to do their business.”3 Picasso had given Kahnweiler something stronger than charm: an art to defend with intellect and love, and an absolute belief in the rightness of his taste. That conviction was his sales technique.

1 See Louis Vauxcelles, “‘Exposition Braque. Chez Kahnweiler, 28 rue Vignon,’ Gil Blas, 14 November 1908,” in Mark Antliff and Patricia Leighten, eds., A Cubism Reader: Documents and Criticism, 1906–1914, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), p. 48. See also Jack Flam, “The Birth of Cubism: Braque’s Early Landscapes and the 1908 Galerie Kahnweiler Exhibition,” in Emily Braun and Rebecca Rabinow, Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014), pp. 22, 302 n.1. On Kahnweiler generally, see Pierre Assouline, An Artful Life: A Biography of D. H. Kahnweiler 1884–1979 (New York: Fromm International, 1991).

2 Assouline, An Artful Life, pp. 49, 368 n.58.

3 Heinz Berggruen, quoted in Philip Hook, Rogues Gallery: A History of Art and Its Dealers (London: Profile Books, 2017), pp. 149–50.

Image © Estate Brassaï–RMN; Pablo Picasso artwork © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy Musée Picasso, Paris; photo: Franck Raux © RMN–Grand Palais/Art Resource, New York

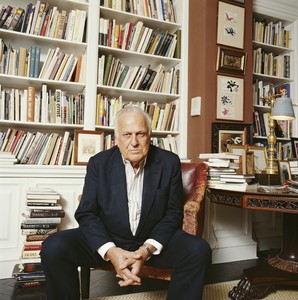

Michael Cary organizes exhibitions for Gagosian, including thirteen Picasso exhibitions in collaboration with John Richardson and members of the Picasso family. He joined Gagosian in 2008 after six years working with the late Kynaston McShine, then chief curator at large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Clive Smith

The Summer 2025 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Pablo Picasso’s Nu accoudé (1961) on the cover.

On April 18, the exhibition Picasso: Tête-à-tête opened at Gagosian, New York. Including works from 1896 to 1972, the full span of the artist’s career, the show is presented in partnership with Paloma Picasso, the artist’s daughter. Here, Michael Cary, one of the organizers of the exhibition, traces the historical precedents that informed the conversational nature of the curation. He also introduces a translation of a 1932 interview with Picasso by the publisher and critic E. Tériade, often quoted in English in part but not in full.

Join president of the Picasso Museum, Paris, Cécile Debray; curator, writer, biographer, and historian Annie Cohen-Solal; art historian Vérane Tasseau; and Gagosian director Serena Cattaneo Adorno as they discuss A Foreigner Called Picasso. Organized in association with the Musée national Picasso–Paris and the Palais de la Porte Dorée–Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris, the exhibition reframes our perception of Picasso and focuses on his status as a permanent foreigner in France.

Cocurator of the exhibition A Foreigner Called Picasso, at Gagosian, New York, Annie Cohen-Solal writes about the genesis of the project, her commitment to the figure of the outsider, and Picasso’s enduring relevance to matters geopolitical and sociological.

Pieter Mulier, creative director of Alaïa, presented his second collection for the legendary house in Paris in January 2022. After the presentation, Mulier spoke with Derek Blasberg about the show’s inspirations, including a series of ceramics by Pablo Picasso, and about his profound reverence for the intimacy and artistry of the atelier.

Pepe Karmel celebrates the release of A Life of Picasso IV: The Minotaur Years, 1933–1943, the final installment of Sir John Richardson’s magisterial biography.

Berit Potter pays homage to the ardent museum leader who transformed San Francisco’s relationship to modern art.

Inspired by a visit to the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s exhibition Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, William Middleton explores the life of this modernist pioneer and her impact on the worlds of design, art, and architecture.

Diana Widmaier-Ruiz-Picasso curated an exhibition at Gagosian, Paris, in 2017–18 titled Picasso and Maya: Father and Daughter. To celebrate the exhibition, a publication was published in 2019; the comprehensive reference publication explores the figure of Maya Ruiz-Picasso, Pablo Picasso’s beloved eldest daughter, throughout Picasso’s work and chronicles the loving relationship between the artist and his daughter. In this video, Widmaier-Ruiz-Picasso details her ongoing interest in the subject and reflects on the process of making the book.

Jenny Saville reveals the process behind her new self-portrait, painted in response to Rembrandt’s masterpiece Self-Portrait with Two Circles.

Picasso biographer Sir John Richardson sits down with Claude Picasso to discuss Claude’s photography, his enjoyment of vintage car racing, and the future of scholarship related to his father, Pablo Picasso.

Mary Ann Caws and Charles Stuckey discuss the presence of food and the dining table in the history of modern art.