Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Summer 2025

The Summer 2025 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Pablo Picasso’s Nu accoudé (1961) on the cover.

Summer 2025 Issue

On April 18, the exhibition Picasso: Tête-à-tête opened at Gagosian, New York. Including works from 1896 to 1972, the full span of the artist’s career, the show is presented in partnership with Paloma Picasso, the artist’s daughter. Here, Michael Cary, one of the organizers of the exhibition, traces the historical precedents that informed the conversational nature of the curation. He also introduces a translation of a 1932 interview with Picasso by the publisher and critic E. Tériade, often quoted in English in part but not in full.

Pablo Picasso, Femme au vase de houx (Marie-Thérèse), 1937, oil and charcoal on canvas, 28 ¾ × 23 ⅝ inches (73 × 60 cm), private collection. Photo: Sandra Pointet

Pablo Picasso, Femme au vase de houx (Marie-Thérèse), 1937, oil and charcoal on canvas, 28 ¾ × 23 ⅝ inches (73 × 60 cm), private collection. Photo: Sandra Pointet

When Picasso was a young painting student in Madrid, he was alarmed by the pressure within the academy to settle on a style and join a “school” of painting. He wrote to a friend in 1897, “I don’t believe in following any particular school, for all it leads to is mannerism and affectation in the painters who do it.”1 It was a radical insight for the young artist, and marked the first inspired turn in a career that would produce the twistiest oeuvre of any painter in history.

The intuitive leap Picasso took was to adopt “no style” as his style. His natural talents and training gave him virtuosity in both mimicry and improvisation, so the young Picasso engaged in what scholars Yves-Alain Bois and Elizabeth Cowling have called a “metaphoric seeing-as”—creating wholly original compositions, but playing them in the key of Velázquez one day, El Greco the next, van Gogh the week after.2 “What does it mean for a painter to paint in the manner of So-and-So or to actually imitate someone else?” Picasso is reported to have asked his friend Hélène Parmelin. “What’s wrong with that? On the contrary, it’s a good idea. You should constantly try to paint like someone else. But the thing is, you can’t! You would like to. You try. But it turns out to be a botch. . . . And it’s at the very moment you make a botch of it that you’re yourself.”3 The essential element of Picasso’s lifelong practice, precisely what keeps his work both relevant and timeless, is his ability to stay fluid, in contradiction, always in restless anxiety and flirting with making a failure of it all.

Pablo Picasso, Femme au béret bleu assise dans un fauteuil gris, manches rouges (Marie-Thérèse), 1937, oil on canvas, 39 ⅜ × 31 ½ inches (100 × 80 cm), private collection. Photo: Sandra Pointet

As history has proved, the gambit was far from a failure. The success of this approach pushed Picasso never to rest on his laurels, never to stop mixing it up, constantly inventing new styles. “Basically I am probably a painter without style. . . .

I shift about too much, I move too often,” Picasso told André Verdet in 1963. “You see me here, and yet I’ve already changed, I’m already elsewhere. I never stay in one place and that’s why I have no style.”4 This was evident in Picasso’s very first exhibition, a show of sixty-four paintings and an unknown number of drawings at Ambroise Vollard’s Paris gallery in 1901. In his review of that show, the critic Félicien Fagus wrote, “One can easily discern . . . numerous probable influences. . . . Each is fleeting, no sooner caught than dropped. . . .The danger for him lies in this very impetuousness, which could so easily lead to facile virtuosity and easy success.”5

Impetuous, yes; but the staggering complexity of Picasso’s oeuvre wasn’t achieved with ease. The truth is, a Picasso exhibition can often be mistaken for a group show—it can appear to be the output of a dozen different artists, rather than of the single prolific polymath that he was. The vastness of his oeuvre underlines the work, the Herculean effort, that it took for one human being to create. Picasso saw this vastness as something not to be tamed but to be exploited and celebrated.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait de Femme (Marie-Thérèse), 1936, pencil, watercolor, and pastel on paper, 13 ⅜ × 10 inches (34 × 25.5 cm), private collection. Photo: Sandra Pointet

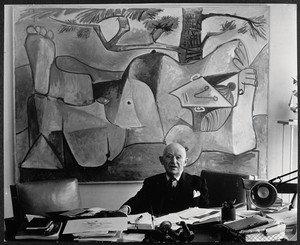

Picasso insisted on choosing the works and arranging the installation of his first retrospective himself. In 1932, the Galerie Georges Petit, on the rue de Sèze, Paris, was old-fashioned, stuffy, déclassé, and long past its heyday. According to Picasso’s biographer John Richardson, though, the artist was thrilled with the venue because the gallery’s “Beaux-Arts look made the shock of the new all the more shocking.”6 Alongside several new paintings created expressly for the show, he secured loans from friends and dealers and included many works taken out of storage that had never been publicly exhibited. When he hung the show, he juxtaposed works of wildly different dates and styles so that they could “talk” to each other. “The mismatching was strategic: Picasso wanted his disparate oeuvre to be seen as an organic whole and not chopped up into arbitrary ‘periods’ by critics and academics, without his authorization,” Richardson writes. “He saw his work as an ongoing family, but members of the same family don’t always look identical.”7 It was a strategy that particularly struck Alfred H. Barr Jr., the young director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, who annotated his photographs of Picasso’s installation to document this phenomenon. “Picasso chose to present his career as one marked by dramatic and irrational changes and extraordinary diversity,” Cowling states, “and as moving not in progressive, linear fashion, but to and fro and round and round, like memory.”8 This is how Picasso intended us to encounter his works—not separated by period or style but in conversation with each other.

Installation view of the exhibition of work by Pablo Picasso at the Galerie Georges Petit, Paris. Photograph annotated by Margaret Scolari Barr and Alfred H. Barr Jr., 1932. Alfred H. Barr Jr. Papers, 12.a.8. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York © G-P. F. Dauberville & Archives, Bernheim-Jeune. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York

Richardson liked to say that with anything one could state about Picasso that was absolutely true, the opposite was equally true. The unpindownable nature of his output also extends to how he spoke about his work. Much as he preferred the provisional, raw-plaster states of his sculptures to their bronze casts, seeing bronze as making them too formal, too set, too “museumy,” he disdained academic critics who set about “explaining” his art with stiff interpretations and concrete categories. A playful confounding of “explanation” is evident in his comments to his friend and publisher E. Tériade while he was in the process of hanging this 1932 retrospective, first published in L’Intransigeant and reproduced here in translation by Nicholas Huckle.

This Thursday will see the opening of an exhibition bringing together more than two hundred paintings, works of sculpture, and engravings by Picasso.

The importance of this painter in the pictorial movement of the past thirty years is well known, as are his audacious experiments in the field of forms.

Picasso has had an impact not only through his artistic work but also through his sparkling intelligence and inventive wit. We include here just a few of his statements, the expression not just of an artist but also of a man.

We were fortunate enough to be able to speak with him as he witnessed his paintings being hung, and we were able to catch a few of his brilliant thoughts as they fell from his lips.

—E. Tériade

Pablo Picasso, Nu drapé, assis dans un fauteuil, 1923, oil on canvas, 51 ¼ × 38 ¼ inches (130 × 97 cm), private collection. Photo: Sandra Pointet

Pablo Picasso, Femme assise au fauteuil rouge, c. 1918, oil on canvas, originally without stretcher, 52 ⅝ × 39 ⅜ inches (133.5 × 100 cm), private collection. Photo: Sandra Pointet

I visited the retrospective at the Salon the other day. This is what I noticed. A good painting in the midst of bad paintings becomes a bad painting. And a bad painting among good paintings ends up being a good one.

Someone asked me how I was going to organize this exhibition. I replied, “Badly.” For an exhibition, like a painting, well or badly “organized,” it all comes down to the same thing. What counts is a certain consistency in the ideas. And when this consistency exists, as with even the most incompatible couples, things always work out.

How many times, when I was about to apply some blue, I realized I didn’t have any. So I took some red and put it down instead of the blue. The mind’s vanity.

Essentially, everything is tied to the self. It is a sun in the belly with a thousand rays. The rest is nothing. It is for that alone, for example, that [Henri] Matisse is Matisse. Because he carries this sun in his belly. And it is also because of this that from time to time something happens.

Painting is a way of keeping a diary.

Installation view of the exhibition of work by Pablo Picasso at the Galerie Georges Petit, Paris. Photograph annotated by Margaret Scolari Barr and Alfred H. Barr Jr., 1932. Alfred H. Barr Jr. Papers, 12.a.8. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York © G-P. F. Dauberville & Archives, Bernheim-Jeune. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York

For a painter at an exhibition who, like me today, sees some of his canvases coming back to him from far away, they seem like prodigal children, returning home clothed in gold.

One always makes paintings the way princes make their children: with shepherd girls. One never does a portrait of the Parthenon; one never paints a Louis XV fauteuil. One paints a shack in the Midi, a packet of tobacco, an old chair.

Front cover of L’Intransigeant, June 15, 1932

At bottom there is only love. Whatever it might be. They ought to put out painters’ eyes as they do goldfinches so that they can sing better.

One of the ugliest things in art is sincerity. It has always soiled the best works because it expresses obedience to everyone.

A friend of mine who is now writing a book about my sculptures begins it like this: “Picasso told me one day that a straight line is the shortest distance between two points.” Naturally I was quite astonished, and I asked him, “Are you sure that it was me who found that out?”

When one starts from a portrait and seeks, by successive eliminations, the pure form, the most reduced and essential volume, one inevitably ends up with the egg. Likewise, starting from the egg and following the opposite path and goal, one reaches the portrait. But art, I believe, escapes this overly simplistic journey from one extreme to the other. Above all, you have to be able to stop in time.

The whole interest of art is in the beginning. After the beginning, it is already the end.

I don’t paint following nature, but in front of nature, with her.

Nothing can be done without solitude. I have created a solitude for myself that no one suspects. It is very hard to be alone today because we have watches. Have you ever seen a saint with a watch? And yet I have looked for one everywhere, even among the supposed patron saints of clockmakers. So, how happy we are right now, engaged in conversation! We might be able to stay like this for years and still find things to say! Ten years from now we would be still here, happy to be here, still talking . . .

Whereupon Picasso took out his watch, saying, “Goodbye, see you soon, I’m expected at lunch.”

1 Pablo Picasso, quoted in Elizabeth Cowling, Picasso: Style and Meaning (London: Phaidon Press, 2002), p. 53.

2 Ibid., 30, referencing Yves-Alain Bois, Matisse and Picasso, exh. cat. (Paris: Flammarion, for the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, 1987), p. 27.

3 Picasso, quoted in Hélène Parmelin, Picasso: The Artist and His Model, and Other Recent Works (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1965), p. 43.

4 Picasso, quoted in André Verdet, Picasso, exh. cat. (Geneva: Musée de L’Athenée, 1963), n.p.

5 Félicien Fagus, “L’Invasion espagnole: Picasso,” La Revue blanche, July 15, 1901, quoted here from Cowling, Style and Meaning, p. 17.

6 John Richardson with the collaboration of Marilyn McCully, A Life of Picasso, vol. 3, The Triumphant Years: 1917–1932 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), p. 475.

7 Ibid., p. 477.

8 Cowling, Style and Meaning, p. 15.

Artwork © 2025 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Picasso: Tête-à-tête, Gagosian, 980 Madison Avenue, New York, April 18–July 3, 2025

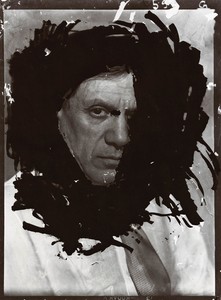

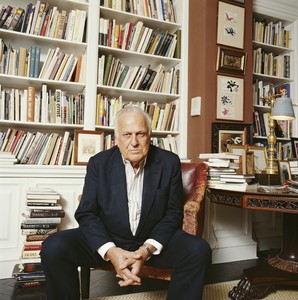

Michael Cary organizes exhibitions for Gagosian, including thirteen Picasso exhibitions in collaboration with John Richardson and members of the Picasso family. He joined Gagosian in 2008 after six years working with the late Kynaston McShine, then chief curator at large at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Clive Smith

The Summer 2025 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Pablo Picasso’s Nu accoudé (1961) on the cover.

Join president of the Picasso Museum, Paris, Cécile Debray; curator, writer, biographer, and historian Annie Cohen-Solal; art historian Vérane Tasseau; and Gagosian director Serena Cattaneo Adorno as they discuss A Foreigner Called Picasso. Organized in association with the Musée national Picasso–Paris and the Palais de la Porte Dorée–Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, Paris, the exhibition reframes our perception of Picasso and focuses on his status as a permanent foreigner in France.

Cocurator of the exhibition A Foreigner Called Picasso, at Gagosian, New York, Annie Cohen-Solal writes about the genesis of the project, her commitment to the figure of the outsider, and Picasso’s enduring relevance to matters geopolitical and sociological.

Pieter Mulier, creative director of Alaïa, presented his second collection for the legendary house in Paris in January 2022. After the presentation, Mulier spoke with Derek Blasberg about the show’s inspirations, including a series of ceramics by Pablo Picasso, and about his profound reverence for the intimacy and artistry of the atelier.

Pepe Karmel celebrates the release of A Life of Picasso IV: The Minotaur Years, 1933–1943, the final installment of Sir John Richardson’s magisterial biography.

Michael Cary pays homage to the visionary dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884–1979).

Berit Potter pays homage to the ardent museum leader who transformed San Francisco’s relationship to modern art.

Inspired by a visit to the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s exhibition Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, William Middleton explores the life of this modernist pioneer and her impact on the worlds of design, art, and architecture.

Diana Widmaier-Ruiz-Picasso curated an exhibition at Gagosian, Paris, in 2017–18 titled Picasso and Maya: Father and Daughter. To celebrate the exhibition, a publication was published in 2019; the comprehensive reference publication explores the figure of Maya Ruiz-Picasso, Pablo Picasso’s beloved eldest daughter, throughout Picasso’s work and chronicles the loving relationship between the artist and his daughter. In this video, Widmaier-Ruiz-Picasso details her ongoing interest in the subject and reflects on the process of making the book.

Jenny Saville reveals the process behind her new self-portrait, painted in response to Rembrandt’s masterpiece Self-Portrait with Two Circles.

Picasso biographer Sir John Richardson sits down with Claude Picasso to discuss Claude’s photography, his enjoyment of vintage car racing, and the future of scholarship related to his father, Pablo Picasso.

Mary Ann Caws and Charles Stuckey discuss the presence of food and the dining table in the history of modern art.