Sarah Sze: Timelapse

Francine Prose ruminates on temporality, fragility, and strength following a visit to Sarah Sze’s exhibition Timelapse at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Winter 2024 Issue

In 2023, Sarah Sze’s immersive video installation Pictures at an Exhibition made its debut at the Thailand Biennale, titled The Open World and codirected by Rirkrit Tiravanija and Gridthiya Gaweewong in Chiang Rai. On the occasion of the work’s inclusion in Sze’s 2024 exhibition at Gagosian, Paris, she met with Tiravanija to discuss thriving in chaos, making room for experiences in time, and her materials.

Left: Sarah Sze. Photo: Deborah Feingold. Right: Rirkrit Tiravanija. Photo: courtesy the artist

Left: Sarah Sze. Photo: Deborah Feingold. Right: Rirkrit Tiravanija. Photo: courtesy the artist

Sarah SzeHow was your flight to Paris?

Rirkrit TiravanijaMy flight was great. I thought I should read a little about your work before our conversation; I like to read what a fellow artist has said, so I can ask them to say more. But, Sarah, you’ve said everything already.

SS[Laughs]

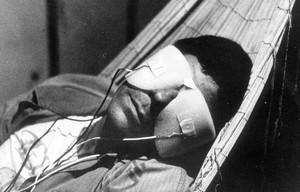

RTI was like, What question could I ask to pry open more stuff? Well, one thing I want to hear more about is your current exhibition, here in Paris. It feels a little like an earlier work of yours, Portable Planetarium [2010]. It feels like you’re exploring planets. When your work Pictures at an Exhibition debuted in The Open World, the piece became the heart of the show, with the clock ticking, beating, in the middle of it all. It was amazing to watch it with the other works: Pierre Huyghe’s film [Untitled (Human Mask) (2014)], which was apocalyptic, like the last person on Earth, you know? And Haegue Yang’s piece [Envelopes Domestic Soul Channels—Mesmerizing Mesh #208 (2023)] about shamanist cures for problems in the world. All of these things were talking to each other. For people who came to that show, many if not most were unfamiliar with art like that, but at the same time, they could totally enter it and relate to it. The imagery is so much of the everyday.

SSThat combination of Haegue’s, Pierre’s, and my work was a really nice curatorial nexus. It was interesting to work with you as a curator—you were completely carte blanche. You had no idea what I was going to make. I actually didn’t know what I was going to make. Then you gave me this huge room alongside these incredible artists, so I had to really make something [laughter]! It was a nice opportunity to do something fast that could be very experimental. I wanted it to be flexible and light and portable. I wanted it to just appear onsite and bloom like a flower.

I’d gone to this talk about the James Webb telescope. They explained how the engineers had got the telescope farther into space: almost like a piece of origami, they brought it out flat and then let it unfold into space. The whole structure was about this kind of unfolding. I love this idea. It reminded me of those oyster shells with paper flowers in them. You put it into water and then a rose grows out of it.

RTIt’s also like those Chinese paper toys that come flat and you blow air into them. I like the element of animation in your work: the movement and life that’s bubbling or boiling or changing. There’s always kineticism, and in this particular work, it’s all there in such a simple way.

SSI wanted it to be like a kiosk, a system that unfolds and provides information anywhere it goes. I always think about the site of a work. Pictures at an Exhibition has this sense that anywhere you bring it, it solves the problems of the space. In this location in Paris, there’s a frame through which you enter the space, seeing a portion of the videos through it. The video in this work isn’t projected on a flat screen, it’s on all of these shredded pieces of paper. But you look through the frame of the entrance and it’s like you’re seeing a moving image through a portal rather than projected on a flat screen. It was an entirely unexpected way to view a film.

And then in the space in Thailand we had these crazy tall doors that made it feel like you were entering an entirely new world. There was this spill of light. It began with a remainder. And then when you entered there was more a compression in the space. The sculpture acted like a magnet and a projector at the same time.

RTTo install a video sculpture without having to black out the room was a great part of it.

SSRight, I didn’t want anything that tells you, “Now I’m going into the art and now I’m coming out.” You just find yourself in it. You find it melds in and out of the real world. It’s in conversation with the architecture, they’re married. Obviously that melding of art with daily life is deeply part of your work too.

RTWe spoke a lot about the idea of wanting an experience in time. People don’t often spend much time looking at art, but with your work you have to spend time. You have to pay attention to little things. We’re currently in a TikTok world, made up of these short little clips, and that’s reflected in your work, but at the same time it also goes much deeper. As a viewer, you can keep watching, plant yourself down, or move around it. It’s really successful that way.

SSIt’s interesting that you brought up TikTok, because of the speed of these timeframes in which we’re fed information. We develop dexterity moving through that timeframe. I think of Doug Aitken’s Electric Earth [1999]; when he made that, everyone was looking at it and thinking, “I know exactly how to read this, but I don’t know why.” I should ask him, but I think it’s because he’d been doing a lot of commercial editing, so it was edited in that way. It was extremely fast, with very short, fast edits, because commercials are dictated by finances. It’s a kind of edit that leaves you wanting more—that timeframe is constant desire, constant longing. It’s the frame of: I’ll show it to you, I’ll give you it, oh, now I take it back. And then you wait to see it again. I was trying to do something similar with the edit for this work, but the sense of time, the pace, of editing and of dealing out information has shifted substantially since the ’90s or even the 2000s.

Sarah Sze, Pictures at an Exhibition, 2023, mixed media, including paper, clamps, string, and stones, overall dimensions variable © Sarah Sze. Photo: Andrea Rossetti

My work is rooted in an exploration of memory. How does something get seared into memory? How is it lost? How is it retrieved?

Sarah Sze

RTWhat I notice is the variety of imagery in the video. You’re making it with so many different genres—it’s an encyclopedia of ideas.

SSThat’s what it was supposed to do: think through how we’ve used film or images to track time. So the variants of ten is a reference to Charles and Ray Eames’s Powers of Ten [1968/1977]. Also Chris Marker’s La Jetée [1962] and Agnes Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7 [1962]. There are direct references to [Eadweard] Muybridge: the experimentation and creation of slow motion by August Musger in 1904, the crowning-of-the-milk image by Harold Edgerton in 1957. No one had ever seen time like that.

RTIn a way you’re turning the history of video art upside down by playing with these different elements.

SSI think artists have this amazing opportunity to look at their work as a lineage of conversation over time. It’s interesting to look at someone like Nam June Paik or Maya Deren, and for me to think what they were doing so brilliantly and then what I want to do differently. It’s educational to look at the work and decide exactly why you’re not going to do that and use that information to define your own work. Scientists have a more formal way of looking at each other’s work and learning from it, they grow off each other’s work. Which is honestly what we as artists do. So for me, looking at Nam June Paik’s work over time gave me the energy to be free from the object. I was more interested in this idea of energy—physical structure is just the tool for the energy to exist. Emphasizing that reminds you of the fragility and the portability of an object. That’s something that’s very interesting in your work, too. You bring something and it’s portable and you set it up, and then you gather it and you go somewhere else and set it up. Like Untitled (lunch box) [1998– ]. It’s a vagabond; it’s got this quality of a traveler.

RTFinding its place again and again.

Could you say a little more about material? Paik addresses the frame of the television; the screen becomes a major theme. And with your work, I was thinking of printmaking because you have digital images, but they’re all projected on paper, not on film or screens. And all the torn edges of the paper are important, right?

SSAbsolutely. It’d be much easier to have those be perfect squares [laughs], but they’re all hand torn. It’s not just the idiocrasy of the paper edges but the rawness of the rips: the feel, the sound, the materiality of it. The paper is material, obviously, but the digital image is material also. It’s like an image appearing on paper the way a print does in printmaking. But in some senses the digital is much more ephemeral. We’ve had paper much longer; we know how to make it last, preserve it. It’s one of the most ancient durable structures we have. With technology, though, the minute you have it, it’s out of date. Museum conservation departments are constantly trying to update the technical equipment in their collections. It’s a huge challenge.

RTIt’s interesting the work doesn’t feel so much about technology. To me it’s more about imagery or light, or the shifting between the two.

SSNo, I think that’s right. I think it’s more about how the image has become material, how we deal with it every day. The image is an everyday object in our life. The fact that I’ll receive 100 images and I’ll probably take at least 50 a day on my phone—we’re totally used to that.

I love that you brought up printmaking. One of my favorite parts of printmaking is when you clean the press and you get ghost prints—you see it disappear as it gets clean. I think it applies to sculpture, too, this idea of a ghost image of something that reappears and disappears. That action is as important as the image itself.

RTIt’s also memory.

SSYes.

Sarah Sze, Crosswalk, 2024, oil, acrylic, archival paper, acrylic polymers, ink, tape, string, diabond, aluminum, and wood, 45 × 40 inches (114.3 × 101.6 cm) © Sarah Sze. Photo: Andrea Rossetti

My world is one with so much information that it’s chaos; you actually have to let go and wander through it.

Sarah Sze

RTIn what I do, people don’t always realize but it’s all about memory. For me it’s always constructed by the person who’s looking, because they come with their own experience in life. What’s interesting about looking at your installation is that it constructs so many different stories, because viewers are all looking at a very different place at different times and they’re remembering very differently.

SSI didn’t realize the work was about memory until I started making it, and now I realize it’s completely rooted in memory. I’m asking, How does something enter your memory? How is it lost? How does it get revived?

What’s fascinating in your participatory installations is this idea of trying to make the work live, to create a live experience. You remind people of the fleeting moment and how we decide to hold on to certain moments. I think all of that intensified after covid, because so much of how we remember time is through chance interaction, serendipity, a meeting with someone else and how that marks time. And when we were isolated and on our screens, our time was more dictated by the scheduled world of Zoom meetings. You never run into a screen the way you run into people on the street, so we had fewer chance encounters during that time.

RTI actually wanted to ask you about the idea of chaos in your work.

SSYes, chaos. I think as artists, we don’t get to choose what kind of work we make. I’d love to be like a painter of small watercolors. I think, Why can’t you do that? Oh, Sarah. But your practice does choose you. I think for me it’s that my world is one with so much information that it’s a chaos, you actually have to let go and wander through it. How you do that is your choice. It’s the same as looking at a piece or at a painting, you’re probably not going to get all of it; you give in to that. You choose things and be with them.

RTWell, that’s my description of utopia. For me utopia is to be able to be in the chaos and not be affected by it. You can sustain yourself with all those commotions and accept it. You never try to hold on to it and you never try to stop or fix things, you just kind of move through it. It’s beautiful.

How do you edit all that chaos, all this imagery, into one cohesive thing?

SSIt’s a growing palette. There are certain things in the video and in the paintings in the show that repeat or relate to each other; they draw from the same archive. It’s really like going to a bookshelf of images—you move them around, you select some and not others; some survive.

RTHow do you create an internal value system: a certain image over another, or a moment in time over another? Those are decisions you make; there are certain things you’re attached to and there are certain things you, like you said, just let go. Does it have to do with your own psyche?

SSI think it doesn’t and does. And like you said, if you ask a viewer, What was the image that lasted for you?, the answer will of course be different for different people—the artwork is giving them an arena of choice. I try to incorporate that nonhierarchical approach in the work. Once it’s made, I kind of distance myself from it, but I also listen to and see how people interact with it.

Personally, in videos and images, I often look for a moment that makes you sort of gasp, take a breath—you know what’s going to happen and you’re still surprised. Like the fox going across a road—I can’t believe that happened. And you can’t plan those things, right? Or you’re walking through a field and all of a sudden you hear birds and they all fly off. When something happens in nature, it’s so profound, because you know it’s by complete chance that you witnessed it.

Sarah Sze: Pictures at an Exhibition, Gagosian, Paris, June 25–September 28, 2024

Since the late 1990s, Sarah Sze has developed a distinct visual language that challenges the static nature of art. Widely recognized for expanding the boundaries between sculpture, painting, video, and installation, Sze uses a complex palette of materials, both analog and digital, to question how we mark time and space. Her work ranges from immersive installations that scale architectures to abstract canvases that explore a constantly evolving visual world. Sze was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2003 and a Radcliffe Fellowship in 2005. She is a professor of visual art at Columbia University.

Rirkrit Tiravanija is known for a practice that overturns traditional exhibition formats in favor of social interactions through the sharing of everyday activities such as cooking, eating, and reading. Creating environments that reject the primacy of the art object and instead focus on use value and bringing people together through simple acts and environments of communal care, Tiravanija challenges expectations around labor and virtuosity. He is on the faculty of the School of the Arts at Columbia University and is a founding member and curator of Utopia Station, a collective project of artists, art historians, and curators.

Francine Prose ruminates on temporality, fragility, and strength following a visit to Sarah Sze’s exhibition Timelapse at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

In this video, Sarah Sze elaborates on the creation of her solo exhibition Timelapse, on view through September 10, 2023. The show features a series of site-specific installations throughout the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, that explore her ongoing reflection on how our experience of time and place is continuously reshaped in relationship to the constant stream of objects, images, and information in today’s digitally and materially saturated world. In Sze’s reimagination of the Guggenheim’s iconic architecture, designed in the 1940s by Frank Lloyd Wright, the building becomes a public timekeeper reminding us that timelines are built through shared experience and memory.

On the occasion of her exhibition of recent paintings, presented at Gagosian in Rome, Pat Steir met with fellow artist Sarah Sze for a wide-ranging discussion—from shared inspirations and influences to the role of chance, contingency, place, and time in painting.

Sarah Sze writes on a recent collage.

The Summer 2020 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Joan Jonas’s Mirror Piece 1 (1969) on its cover.

Hear Sarah Sze speak about her most recent work, including the panel painting Picture Perfect (Times Zero) and the multimedia installation Plein Air (Times Zero) (both 2020). Discussing the relationship between painting and sculpture in her practice, she explains how she creates structure and its inverse, instability, in her layering of images, putting the viewer in the position of active discovery.

Sarah Sze writes about five films that live as richly evocative images in her visual memory.

Louise Neri talks with Sarah Sze about the new primacy of the image in her explorations between and across mediums. They spoke on the occasion of an exhibition of Sze’s work at Gagosian, Rome, comprising collaged panel paintings, a large-scale video installation, and an outdoor sculpture fashioned from a natural boulder.

Join Sarah Sze as she talks about the questions that drive her work. She describes creating immersive experiences that blur the lines between time, memory, and space—and between art and life.

The inaugural presentation of Frieze Sculpture New York at Rockefeller Center opened on April 25, 2019. Before the opening, Brett Littman, the director of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum and the curator of this exhibition, told Wyatt Allgeier about his vision for the project and detailed the artworks included.

Join Sarah Sze in her studio as she prepares for an exhibition of new work in Rome.

On the eve of ECHOES FROM COPELAND, an exhibition of new paintings at Gagosian, New York, Nathaniel Mary Quinn met with Ashley Stewart Rödder to discuss the genesis of the works he’s been creating, their literary origins, and his evolving approach to the practices—and intersections—of painting and drawing.