Glenn BrownI thought IMAGINE! 100 Years of International Surrealism was an important show, in part because it included artists who were not known to be connected to the Surrealist movement, especially a number of women artists who were historically excluded from the “Surrealist Manifesto” and André Breton’s idea of Surrealism. And honestly, including works made by these artists just makes Surrealism look a lot better. It is important to mention that the exhibition’s other great concept is that Surrealism started in the 1870s with Symbolism and Symbolist arts, and of course Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams (1899) and all of his writings on the importance of the unconscious mind. One could argue that it was really Freud who kick-started Surrealism, way before André Breton introduced the idea in 1924.

Your work is full of references to Surrealism. You aren’t necessarily trying to make it look like Surrealist art, but rather you seem to be using ideas related to the unconscious, symbolism, and metaphor. The dream world seems really important to you.

Alexandria SmithI appreciate how you see that in my work. Other artists have seen it too, but critics and scholars haven’t talked about it. I am absolutely drawing on Surrealist symbolism. A lot of what I read is inspired by Surrealism, or magical realism, as the literary genre is called. You and I both allow that sensibility to infuse our work. I’m curious to hear your perspective as well. We’re from two different generations, so your introduction to Surrealism and its context was likely different from mine. Over the decades, many artists have brought the surreal into their work without it being addressed, especially when it comes to artists of color. Caribbean Afro-Surrealist artists and writers, for instance, have been erased from the conversation. Just think about how much time Suzanne and Aimé Césaire spent with André Breton. They were all working together to resist colonization and trying to find ways through Surrealism toward revolution and emancipation, even though they were in different parts of the world, namely the Caribbean and Europe.

GBLately I’ve been thinking about Sun Ra as a mix of Surrealism and science fiction, visually and in music.

ASSun Ra’s been labeled an Afro-Futurist because he was drawing on science fiction and technology, but he’s definitely part of this conversation.

GBI like his open, “what if” sensibility. It’s why I use images from the past to comment on the future.

ASHow are you doing that? How are you mining the past with an eye toward the future?

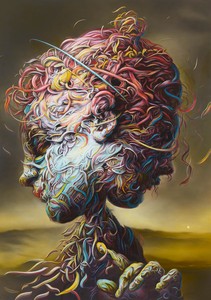

GBI tend to make work for an imagined future audience. My paintings can take several years, so in a fast-moving world I can’t be absolutely contemporary, but how it feels to be human is fairly consistent. I have this idea that people from the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries and people today have similar emotions—hopes and dreams that are extraordinarily alike. I lift portraits from the past and transpose them to the present day or the future by altering the way they’re painted, especially the color rationale.

ASIn my work, the color becomes its own character. It’s another subject in the composition.

GBWhere do you get your colors from? The real world? Because you use color beautifully, and not just in terms of push-pull and composition. You often use very gray backgrounds or figures, placing them amid brightly colored elements.

ASMy color is both internal and external. I’m influenced by the environments I inhabit. For example, the work I made in London these past four years has a very different color palette than work from before I moved to London. I’m drawing color from my emotional state, but also from the present moment, wherever I am in the world geographically. I think about color as a way of collectively imagining and relating to one another.

GBWhen you say “internal,” do you mean emotionally internal or physically internal?

ASEmotionally internal. Physically internal—sometimes that comes out, but it’s rare. The characters in my work are usually avatars or stand-ins for emotional states of being. The grays, blues, and cool colors, they came about when I moved to London.

GBThe grays from London!

ASYeah, London hit me over the head with that. [laughter] I didn’t have much of a choice but to embrace it.

GBDo you ever wake up in the morning or in the middle of the night with a great idea for a composition or a subject for a painting? Because your work has a sense of the dream state.

ASFor sure, there are times when I wake up with an idea, or I see something right before I go to sleep and need to write it down or sketch out the idea, however roughly. Sometimes it happens in meetings. When I’m supposed to be paying attention, I’m daydreaming about new compositions.

GBI get my best painting ideas very late in the evening, when I’m not asleep but my brain is starting to go into that mode. My thoughts are free and I get wilder, more interesting ideas.

ASThat happens to me a lot in airplanes. Or when I’m driving. When my body’s in transition or on the move.

GBWhy do you think that is?

ASI attribute it to habit. Doing something routine, something I’m used to doing, allows my imagination to get activated.

GBThe unconscious can kick in.

ASI’ve heard that from writers especially. A lot of writers I know get ideas when they’re in transit.

GBThat’s definitely not the case for me. I tend to be in the studio when ideas occur. But then again, I come up with paintings in a very different way. My works are all based on other artists’ works. I have a huge library of books, so I constantly refer to images or cross-reference things. Put one painting next to another to see what happens when I mix the two together. My dreaming is done in terms of the way I play with images.

ASYou’re a collagist and a DJ. Actually, I think we can both own those titles. [laughs] We’re constantly remixing things. I’m remixing language when I’m coming up with titles, but I’m mostly remixing my own work. I’m pulling from iconography of the past and remixing it to create something new, as in collage—a key practice in Surrealism. And you’re doing something like that with other artists’ work, as well as your own.

GBI do refer to my own work an awful lot when I’m making a painting.

ASYour titles are very unique and unexpected, like The Hurdy-Gurdy.

GBThat’s a sculpture. A hurdy-gurdy is a very basic machine for making music. You turn a handle, sort of like a mechanized accordion. Street musicians used to play them for money. I liked that the title would refer to sound and a poor street entertainer. Another sculpture I’ve done is titled Hey Nonny Nonny / The Busker’s Empty Cap. “Hey nonny nonny” refers to Shakespeare; it’s a nonsense rhyme he used for his singers. He wrote “Hey nonny nonny,” and the performers could swap in their own lines if they wanted. Adding the busker’s empty cap alludes to the idea that the street performer is failing to entertain, since the cap is empty of money. Performance and failure—it’s a comic idea of what it’s like to be an artist. It’s a way to create pathos.

ASThen you’ve got Bikini.

GBThere are two ways of looking at that title. You can see it as conjuring a swimsuit and a beautiful sunlit beach. But I think more of the French designer who, in 1946, cut out the middle of a one-piece swimsuit and observed, “Oh, it’s like splitting the atom.” He named it after Bikini Atoll, the islands where the United States was holding nuclear bomb tests. Those beautiful islands were destroyed by nuclear testing. Nobody can live there now. So you’re meant to think about a swimsuit and being on a beach and a nuclear holocaust all at the same time.

ASThose polarities!

GBMarcel Duchamp said that adding a title to a work gives the artist an opportunity to add an invisible color. How do you come up with your titles? They’re very powerful; you must consider them carefully.

ASThank you. Yes, they’re another part of the work for me. They’re really important—a way to bring another layer of meaning, another element of depth and iconography. They usually come to me after the work is done. I’m always grabbing snippets of phrases from books, book titles, poetry, overheard conversations.

GBWhere did you get a title like Heft of the Lumens?

ASInitially it wasn’t Heft of the Lumens, it was just The Lumens. I was thinking about the figures with their concentric circles, or the orb of light around the eyeballs. They’ve evolved over the years through different bodies of work. But for Heft of the Lumens, I was thinking about weight and gravity. The figures look like they’re swimming, but they could be drowning or getting pulled down. Then there is a shadow—you’re not sure if there are three figures or two, or perhaps one figure and a shadow. I like to play with those dualities. And I wanted the title to literally reflect the weight. So The Lumens didn’t feel complete.

GBIt’s a beautiful metaphor for the way you make a painting, because heft involves weight, and light has no weight at all. You put these incongruous elements together, and you get this resonance—or perhaps rather dissonance, because it doesn’t make sense. That’s what images can do; they can make sense of nonsensical elements.

ASDefinitely. You use line in your work to do something similar. I wonder if you could talk a bit about that, like how you arrived at an approach to painting that feels very much like drawing.

GBOne of the nice things about drawing is that you can make an object out of lines that feels absolutely solid but translucent at the same time. It allows me to have one image overlaid with another, and it challenges your brain to make sense of something that shouldn’t be sensible. Line drawing became very important to me because it gave me freedom to make images that could be free-floating. I like the idea of escaping gravity, and I think you do as well.

ASDefinitely, we have that in common.

GBI suppose that comes from the dream world too, that you could be free somewhere that you’d normally be weighed down.

ASI think about the in between of things, of spaces, of time, and how that has so much weight, but also the idea of being in flux or a liminal space, when you’re not solidly in one place or another.

GBWhen you say “in between,” what do you mean?

ASMeaning, you can physically inhabit one space but also psychologically or spiritually inhabit another. I think the spiritual or the subconscious is that in-between state.

GBIt’s a state of reverie, which you want to be in sometimes. It’s not between good and bad, light and dark, up or down, necessarily. Or maybe it’s between all of those things at once. Between heaven and hell.

ASIt’s hard to articulate, but it’s something like that. People have such binary ways of thinking. Everything has to be either/or, never both/and.

GBI think it’s quite important to tell people that you can have both sides of a story, and both can be right.

ASIt provokes deep thought. Thinking about the in-between state of things slows you down. That’s what we’re doing in our work by bringing in Surrealism—hopefully igniting thought, feeling, and emotion, but also slowing people down.