Now available

Gagosian Quarterly Fall 2025

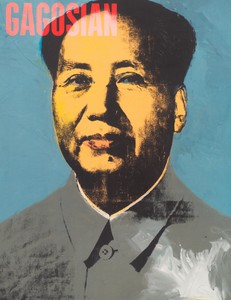

The Fall 2025 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Andy Warhol’s Blue Liz as Cleopatra (1962) on the cover.

Fall 2024 Issue

Jessica Beck examines Andy Warhol’s return to painting in the 1970s, focusing on the artist’s Mao series.

Andy Warhol, Mao, 1972, acrylic, silkscreen ink, and pencil on linen, 176 × 135 ⅞ inches (447 × 345 cm)

Andy Warhol, Mao, 1972, acrylic, silkscreen ink, and pencil on linen, 176 × 135 ⅞ inches (447 × 345 cm)

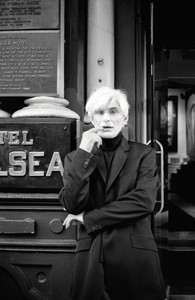

Paul Taylor: What do you ever see that makes you stop in your tracks?

Andy Warhol: A good display in a window. . . . I don’t know . . . a good-looking face.

Taylor: What’s the feeling when you see a good window display or a good face?

Warhol: You just take longer to look at it. I went to China. I didn’t want to go, and I went to see the Great Wall. You know, you read about it for years. And actually it was great. It was really really really great.1

Glenn O’Brien: Who has the best gossip?

Warhol: Actually, I think the newspapers have the best gossip.2

Out of the slew of texts, reviews, and essays on Warhol’s work, the 1970s remain one of the most eclipsed decades of his career. Since his passing, in 1987, his 1950s commercial and BoyBook drawings have seen success, and the work of the 1960s, without a doubt, remains his most lauded and admired. His Silver Factory has become cultural lore and the underground wonderland that he built with his Superstars still attracts screenwriters, product placement, and imitation from popular culture. The 1980s collaborations with Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, and his last chapter of the Last Supper paintings, have seen expanded research, but his output of the 1970s seems to achieve only a tepid response in the archive—it’s the period that many like to skip over or hesitate to unpack. Yet this was the moment when he daringly returned to painting, approaching the canvas with great enthusiasm and sophistication. During this lost decade, he challenged himself to paint differently and reenlivened his career. The Mao series is the heroine of his fresh start.

After Warhol was shot and nearly killed, in 1968, his production model changed. Fred Hughes’s role as his business manager became fixed, and Hughes introduced an emphasis on contracts and deals that promised a steady income to maintain the studio production and payroll. During this era, Warhol worked closely with such dealers as Ileana Sonnabend, Leo Castelli, and Bruno Bischofberger. And while he remained successful in Europe, mostly from these commercial relationships,3 his friendship with the fashion designer Halston and growing alignment with the fashion world, his proximity to celebrities, and his frequent appearances on the VIP balcony of Studio 54 seemed to sully his name with art critics.4 In 1972, four years after his shooting, Warhol expanded his endeavors beyond the canvas with Interview magazine, film production, opportunities in Hollywood, the Andy Warhol Diaries and Popism books—but Hughes was pushing him to return to painting full-time.

Andy Warhol, Mao, 1972, acrylic, silkscreen ink, and pencil on canvas, 82 × 60 inches (208.3 × 152.5 cm)

The Mao paintings started with Bischofberger, Warhol’s Swiss dealer, who along with Hughes was encouraging him to paint again. In an often cited exchange from Bob Colacello’s book Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up (1990), Bischofberger suggested that Warhol paint the most important figure in the twentieth century, who in his mind was Albert Einstein.5 To this suggestion Warhol quipped, “That’s a good idea. But I was just reading in Life magazine that the most famous person in the world today is Chairman Mao. Shouldn’t it be the most famous person, Bruno?” Fame was already a trademark of Warhol’s practice, but for Warhol fame wasn’t linked solely to Hollywood or to expertise: it came from the currency of a star’s image across a broad range of media channels, and from the hold of that image over the national consciousness.

At the moment when Warhol expressed interest in Mao Zedong, the chairman’s face was all over the media. Not only had Warhol seen him on the March 3, 1972, cover of Life, he would have also seen the chairman during the widely televised trip that Richard Nixon had taken to China a month earlier. The first ever visit to China by an American president, Nixon’s trip marked a historical turning point in global politics, with the Americans and the Chinese opening to one another after a quarter-century of bitter hostility. Nixon famously called the journey “the week that changed the world.” On the cover of Life that Warhol remembered was a photograph of the chairman, slouched in an armchair and looking aged and overweight, during his first televised meeting with Nixon and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger. The headline below read “Nixon in the Land of Mao.” Warhol’s interest in Mao landed at the moment of a great media swell and reveals his keen interest in press coverage and headlines. This same impulse was the driving force behind his iconic paintings of Marilyn, Liz, and Jackie from the early 1960s, works made from photographs sourced during periods of frenzied media coverage and public crisis. As with these women that he had immortalized then, Warhol chose an image of Mao with emblematic weight and power: not the photo on the cover of Life, but a portrait in an American edition of Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, commonly known as the “Little Red Book”—the very image that hung over Tiananmen Square and in the consciousness of the geopolitical world.6 With his signature silk-screen and vibrant palette, Warhol transformed this controversial leader into a Pop icon.

The success of these stunning paintings is this mix of high and low, this blurring of the lines between reverence and fashion.

Jessica Beck

Between 1972 and 1973, Warhol painted five series on the chairman, in graduated sizes. His palette became more vibrant and varied during this period, and his brushstrokes more animated; as the series progressed, the paintings morph into studies of color and abstraction. Warhol started the first group of eleven paintings in March of 1972, within a month after the publication of that issue of Life magazine. At eighty-two by sixty-two inches, these works are modest in scale, and Mao is fashioned in a consistent palette, against a complementary blue background, and with a vibrant pop of red on his lips. This early series exudes elegance, reverence, and stateliness. In several canvases from this group, Warhol darkens the right side of Mao’s face, hinting at a self-portrait of his own, from 1966, that obscures one side of his face in shadow.

Eight months later, in November and December, Warhol doubled the scale and created four giant Mao works at a commanding 177 by 137 inches. Here he softened his palette, implementing a paler blue, a lighter gray, and turning the chairman’s face from pink to yellow. The background received only touches of feathered brushstrokes to the top and bottom of the canvas. As Warhol continued to paint in three more sizes into 1973, Mao’s facial highlights were lost to heavy, swirling brushstrokes around his head, background, and shirt, brushstrokes that dominate the canvases. With the giant Mao paintings, the scale does more of the work, and the restrained brush brings attention to the chairman’s face.

Installation view, featuring Andy Warhol’s Mao (1972), 34th Biennial of American Painting, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, February 22–April 6, 1975. Photo: Pascal Falligot

The size of the four giant Mao’s pays homage to the towering portrait of the chairman that still stands in Tiananmen Square, an image that Warhol at this point would have seen only on television or in photographs but that was, of course, top of mind following Nixon’s meeting with the leader. Nixon had also toured the Great Wall and visited the zoo, marking the beginning of over fifty years of “panda diplomacy”—China’s good-will practice of lending giant pandas to American zoos. But the painterly, gestural abstraction of the works, and their significant scale, gives them life and highlights their physicality, which is noteworthy given that Warhol had spent the first part of this decade recovering from his post-shooting surgeries. The result is a luminous portrait of a complicated figure, whom Warhol’s brush softens. Mao’s face is a yellow peach, his communist uniform is a feather gray, and his eyes are highlit with blue and his lips with petal pink, giving his expression and features a gentle feel, one might even argue a feminine one. The subtle touches of color in the lips, which are also crossed by a touch of red, suggest the hint of a smile and recall the slight animation of the lips of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (c. 1503–6), an expression that has captivated the public’s attention for centuries. Just as Warhol chose Mao at a time of great media attention, he painted his first Mona Lisa in 1963, during the painting’s historic tour from the Louvre to the National Gallery in Washington. As if plucking Mona Lisa and Mao from the public spotlight, Warhol added each figure to his roster of Superstars. Mao, here, was recast as one of his beauties.

The curator and collector David Whitney brought three of the four giant Mao paintings together for the first time in his 1979 exhibition Andy Warhol: Portraits of the 70s, at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. Critics were unimpressed by Warhol’s society portraits; writing in the New York Times, Hilton Kramer called the works in the show “embellished photographic blowups—mainly silk-screened images sporting gaudy color and smeary brushwork,” with “shallow and boring” results.7 Warhol’s work, he continued, “belongs less to the history of painting than to the history of publicity.”8 Yet the giant Mao works made an impact. Kramer described the installation as a chapel-like pavilion, which aligns with Robert Rosenblum’s religiously toned description in his essay in the Whitney’s catalogue, where he writes, “Warhol has located the chairman in some otherworldly blue heaven, a secular deity of staggering dimensions who calmly and omnipotently watches over us earthlings.”9 The success of these stunning paintings is this mix of high and low, this blurring of the lines between reverence and fashion. Just as he described newspapers as his favorite gossip columns, his paintings of Mao are a fashion fantasy in which an authoritarian leader becomes a political deity.

Richard Nixon and Mao Zedong, 1972. Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images

Nixon’s trip to China was not the first time television played a defining role in his career: in 1960, a decade earlier, it was his four televised debates with John F. Kennedy that ruined his first attempt to win the presidency. Nixon was no match for the well-groomed, camera-friendly Kennedy, who understood the power of wide appeal. Years before his time in the White House, Kennedy projected himself as a man of letters and of the arts, and as he rose in national attention he became a powerful symbol of family ideals as well as a charismatic sex symbol.10 The advent of the televised debate marked a significant union between entertainment and politics, between Hollywood and the White House, and the first time in history that camera presence could sway an election.

Warhol had keen insight into the construction of an image and the power and importance of the process. His entire career rested on this principle, and his own self-image was proof of his mastery at concealing, shadowing, and duplicating. The debates between Kennedy and Nixon resurfaced in contemporary culture following President Joseph Biden’s disastrous performance during his first televised debate with former President Donald Trump during the 2024 campaign: Biden lost his train of thought, stumbled and flubbed words, and the impact of his advancing age was laid bare for the entire world to see. Warhol’s Mao series are reminders of why we keep returning to his work, because he mirrors back to us our obsession with fame and our fetish for images. He undresses the world of illusions we’ve created with social media, where appearances reign superior to ideas. The charisma of the Mao series endures and marks Warhol’s recovery in the 1970s, his comeback, and the way he found his way back to great painting. In fact he overshadows the political titan: one might rewrite the Life magazine headline as “Mao in the Land of Warhol.”

1 Paul Taylor, “Andy Warhol: The Last Interview,” 1987, in Mark Francis, Andy Warhol: The Late Work, exh. cat. (Munich and New York: Prestel, for the Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf, 2004), p. 121.

2 Glenn O’Brien, “Interview with Andy Warhol,” High Times, August 1977, repr. in Francis, The Late Work, p. 62.

3 See Neil Printz and Sally King-Nero, eds., The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné: Paintings and Sculptures 1970–1974 (London and New York: Phaidon, 2010), 3:182.

4 The critic Robert Hughes, for example, wrote of Warhol’s exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in 1979, “Warhol’s admirers, who include David Whitney, the show’s organizer, are given to claiming that Warhol has ‘revived’ the social portrait as a form. It would be nearer the truth to say that he has zipped its corpse into a Halston, painted its eyelids and propped it in the back of a limo, where it moves but cannot speak.” Hughes, “Art: Mirror, Mirror on the Wall,” Time, December 3, 1979. Available online at https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,948645-1,00.html (accessed July 27, 2024).

5 See Bob Colacello, Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up, 1990 (repr. ed. New York: Vintage, 2014), p. 149.

6 See Printz and King-Nero, eds., Paintings and Sculptures 1970–1974, 3:166.

7 Hilton Kramer, “Art: Whitney Shows Warhol Works,” New York Times, November 23, 1979.

8 Ibid.

9 Robert Rosenblum, “Andy Warhol: Court Painter to the 70s,” in Whitney, Andy Warhol: Portraits of the 70s, exh. cat. (New York: Random House and Whitney Museum of American Art, 1979), p. 20.

10 See Mark White, “Apparent Perfection: The Image of John F. Kennedy,” History 98, no. 2 (330) (April 2013): pp. 226–46.

Artwork © 2024 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jessica Beck is a director at Gagosian, Beverly Hills. Formerly the Milton Fine Curator of Art at the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, she has curated many projects, notably Andy Warhol: My Perfect Body, the first exhibition to explore the complexities of the body, through beauty, pain, and perfection, in Warhol’s practice. Photo: Abby Warhola

The Fall 2025 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Andy Warhol’s Blue Liz as Cleopatra (1962) on the cover.

Carlos Valladares tracks the artist’s engagements with Hollywood glamour, thinking through the ways in which the star system and its marketing engine informed his work.

The Fall 2024 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring Andy Warhol’s Mao (1972) on the cover.

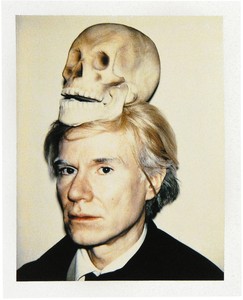

Andy Warhol’s Insiders at the Gagosian Shop in London’s historic Burlington Arcade is a group exhibition and shop takeover that feature works by Warhol and portraits of the artist by friends and collaborators including photographers Ronnie Cutrone, Michael Halsband, Christopher Makos, and Billy Name. To celebrate the occasion, Makos met with Gagosian director Jessica Beck to speak about his friendship with Warhol and the joy of the unexpected.

In this video, Jessica Beck, director at Gagosian, Beverly Hills, sits down to discuss the three early paintings by Andy Warhol from 1963 featured in the exhibition Andy Warhol: Silver Screen, at Gagosian in Paris.

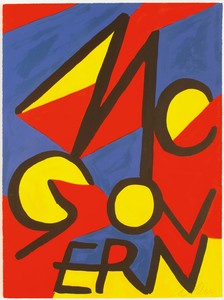

Against the backdrop of the 2020 US presidential election, historian Hal Wert takes us through the artistic and political evolution of American campaign posters, from their origin in 1844 to the present. In an interview with Quarterly editor Gillian Jakab, Wert highlights an array of landmark posters and the artists who made them.

Raymond Foye speaks with the actor who impersonated Andy Warhol during the great Warhol lecture hoax in the late 1960s. The two also discuss Midgette’s earlier film career in Italy and the difficulty of performing in a Warhol film.

Jessica Beck, the Milton Fine Curator of Art at the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, considers the artist’s career-spanning use of Polaroid photography as part of his more expansive practice.

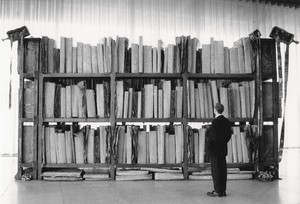

Rare-book expert Douglas Flamm speaks with designer Norman Diekman about his unique collection of books on art and architecture. Diekman describes his first plunge into book collecting, the history behind it, and the way his passion for collecting grew.

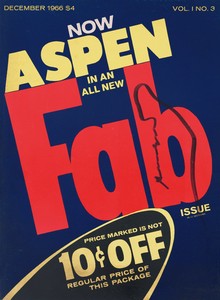

Gwen Allen recounts her discovery of cutting-edge artists’ magazines from the 1960s and 1970s and explores the roots and implications of these singular publications.

James Lawrence explores how contemporary artists have grappled with the subject of the library.

The Winter 2019 issue of Gagosian Quarterly is now available, featuring a selection from Christopher Wool’s Westtexaspsychosculpture series on its cover.